Content

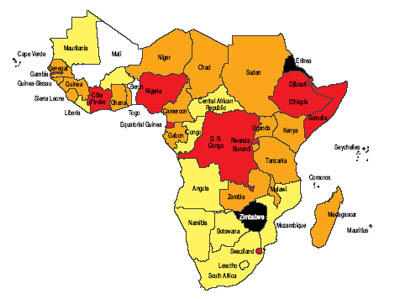

Introduction Africa

Introduction Africa – Annual Report 2006

by Reporters Without Borders

Impunity, a continental ill

In Africa, impunity is not a matter of bad luck, it is the general rule. In Burkina Faso, those who murdered journalist Norbert Zongo in 1998 spend their days in tranquility. The investigation has been stalled by the law of silence that surrounds the presidential guard and François Compaoré, the brother of the president, who has been implicated in this case. In Gambia, the killers of Deyda Hydara, gunned down in 2004, have every reason to enjoy peace of mind. They run absolutely no risk of arrest. President Yahya Jammeh is too busy sullying the memory of the victim, as well as humiliating and threatening journalists. Nothing has been heard of Guy-André Kieffer, kidnapped in Cote d’Ivoire in April 2004, since he fell into a trap set by Michel Legré, the brother-in-law of the wife of President Laurent Gbagbo. Released after 18 months in custody, Michel Legré has pointed the finger at the head of state’s entourage. But the French magistrates appointed to the case have failed to complete their investigation, in a politically poisonous climate. Even in Mozambique, where the murderers of Carlos Cardoso, who was ambushed in 2000, received heavy sentences, the wounds caused by this tragedy have still not fully healed. It is still not known whether the son of the former president Joachim Chissano, Nyimpine, has any link with the case. In the Democratic Republic of Congo, Acquitté Kisembo, who worked for Agence France-Presse, is still posted as “missing”. But he was almost certainly murdered by one of the militias that operate in the east of the country.

Impunity is also political. Countries systematically crack down on the press without being called to account by anyone. For more than five years, a closed and gagged Eritrea has been an open air prison. The least hint of opposition is punished by imprisonment. Thirteen journalists were sent to languish in jail, in a climate of general indifference, one week after 11 September 2001. But the threat of a new war with Ethiopia has allowed President Issaias Afeworki to escape any sanctions. As for the president of Zimbabwe, Robert Mugabe, a nationalist autocrat who brooks no discordant voices, benefits from the benevolent protection of Thabo Mbeki, president of a South Africa that has become the continent’s superpower. Rather than support democratic movements, the country of Nelson Mandela prefers to play the role of guardian to a despot in the name of African sovereignty. The Democratic Republic of Congo has experienced a wave of murders of journalists which have not caught the attention of the UN or the European Union, both busy organising elections. Prime Minister Meles Zenawi, in Ethiopia, for his part, viewed demonstrations in November as an attempted armed insurrection organised by the opposition and its press. In an immediate reaction, opposition leaders and editors of some newspapers were arrested and faced with charges of extreme gravity, not to say absurdity, notwithstanding the fact that Addis Ababa is the headquarters of the African Union. In Rwanda, the government and party of Paul Kagame use and abuse draconian laws and the fear of “sedition” to hound any journalists who are too independent for their taste. The people’s gacaca courts set up to try some of those charged with genocide, are sometimes used for score-settling. No country dares challenge the government directly, relations with the international community are still marked by the horrifying memory of the 1994 genocide. As for the “hate media” of Cote d’Ivoire, they continue to bellow their message freely in a country that has been paralysed and corrupted by civil war. Moderate journalists have to rub along with intolerable colleagues. In Teodoro Obiang Nguema’s Equatorial Guinea no excuses need to be given for the desert for freedoms that the government runs. No-one talks about freedom of the press to the head of “Africa’s Kuwait”. In the small kingdom of Swaziland of the absolute monarch Mswati III, freedom of press is a fantasy. Publishing the truth is a crime and that does not appear to bother anyone.

Even if Nigeria has left behind the dark years of the military juntas, journalists can only suffer in silence the state security’s beatings and heavy-handed searches. Nothing is done to oblige the police to respect press freedom, for which the government displays a sovereign indifference. To a lesser extent, police officers in Gabon and Guinea can continue to beat journalists doing their job; since these are the orders they are given. On the other side of the continent, the new government in Somalia is trying to rebuild a nation on the basis of an archipelago of domains defended by armies of the unemployed. But the clan chiefs have no hesitation in attacking journalists who inform the people despite the anarchy. At the best they are banished. At the worst they have them killed.

Daily injustice

African journalists are also confronted with that other form of impunity that is injustice, whereby the guilty can be rewarded and the innocent punished. In countries such Zimbabwe, Democratic Republic of Congo, Rwanda, Cameroon, Madagascar, Uganda, Malawi, Seychelles, Zambia, Lesotho, Niger, Chad and Sierra Leone, defamation or publishing false news are considered to be crimes. On the basis of one complaint and if the person lodging it should be influential or have influential allies, the police take a cunning pleasure in arresting journalists as if they were robbers. No matter that the subsequent trials prove them innocent. They will have been in prison for 24 hours or for several weeks. Where corruption is the general rule, the best way to avoid being thrown into a prison cell is to applaud ministers, officials and businessmen.

Reporters Without Borders has not let up in its pleas to governments to put an end to these practices and change their laws. Togo, Angola, and the Central African Republic have done so and are better for it. The press, which regulates itself through representative bodies, has acquired responsibility and relations with government are no longer marked with rancour and the spirit of revenge. The problems that continue to beset the press are more likely to be linked to a heritage of violence and political hatreds that sometimes make journalists the targets of those who are unaccustomed to the rules of democracy. The governments of Senegal, Madagascar and Niger, have frequently made convincing sounding promises to decriminalise press offences – but only later, when they no longer feel the need to send the police to punish journalists who have crossed the “red lines”.

Freedom in a few places

Some governments prefer to allow the status quo to continue on the convenient pretext that they have to deal with situations in which violence can easily be stoked up. They fail to understand that it is injustice that creates the danger. Others, like Benin, Mali, Burkina Faso, Namibia, South Africa, Botswana, Tanzania, Burundi, Ghana, Liberia, the Comoros and Congo-Brazzaville, ensure a satisfactory degree of press freedom despite episodes of violence and harassment. In cases brought before the courts, the law is applied with care and relative fairness. As a result, press offences do not give rise to the international reactions provoked by the imprisonment of a journalist, who whether admirable or mediocre, automatically becomes a martyr. Prison sentences for press offences are disproportionate and counter-productive.

African governments seem to have understood. The 3 August palace revolution in Mauritania brought to power a team who set their goal as creating a democracy to replace the “private domain” of ousted president Maaouiya Ould Taya. It is a mammoth task that includes justice and law reform, in which Reporters Without Borders is actively taking part, alongside journalists in a country that was one of the most repressive on the continent. The situation in Chad has opened up after a dark year for the press. Following an on-the-spot investigation, while four journalists were in prison, Reporters Without Borders suggested an amendment to the law and negotiations between the journalists’ union and the government have begun, in a political context that is nevertheless extremely dangerous. In Sudan, where guns still do the talking, the formation of a government of national unity has allowed President Omar al-Bashir to take a historic step – abolishing emergency laws and lifting censorship. Pressure produces results.

But these areas of progress are rare and fragile. Solidarity with Africa is not just a question of food and money. Solidarity should also mean insistence on the rule of law. To close one’s eyes to trampled freedoms, to get used to violence, become inured to political murders, is to approve them and accept that there are people deserving of justice and others deserving of oppression. In Gambia, a Reporters Without Borders representative was told by a friend of Deyda Hydara, “If you forget us, they will do what they want with us”.

Club of Amsterdam blog

| Club of Amsterdam blog October 26: Synthesis of elBulli cuisine October 14: The new Corinthians: How the Web is socialising journalism September 20: A Future Love Story |

News about the future of Ethics in Journalism

State of the News Media 2006

The State of the News Media 2006 is the third in an annual effort to provide a comprehensive look each year at the state of American journalism.

Scan the headlines of 2005 and one question seems inevitable: Will we recall this as the year when journalism in print began to die?The ominous announcements gathered steam as the year went on. The New York Times would cut nearly 60 people from its newsroom, the Los Angeles Times 85; Knight Ridder’s San Jose Mercury News cut 16%, the Philadelphia Inquirer 15% – and that after cutting another 15% only five years earlier. By November, investors frustrated by poor financial performance forced one of the most cost-conscious newspaper chains of all, Knight Ridder, to be put up for sale.

“The study, which we believe is unique in depth and scope, breaks the news industry into nine sectors (newspapers, magazines, network television, cable television, local television, the Internet, radio, ethnic media, and alternative media) and builds off many of the findings from a year ago.”

The study is the work of the Project for Excellence in Journalism, an institute affiliated with Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism.

The Future of News: A Challenge to Both Sides of the House

Rick Edmonds, Poynter Researcher and Writer: “A bright future for newspapers depends on two things that may sound the same but are actually different:

(1) Editors and newsroom staff must continue as the primary news providers in their communities, adapting and delivering reports on multiple platforms, innovating in form, voice, variety and audience-focused content.

(2) As businesses, newspapers must generate new sources of income as traditional ones fade. That includes online display advertising, rich and competitive local classified, local search, other online income and multiple niche publications. They must also get the best results — discovering new lines of business and holding on to the old — in the paper edition.”

News about the Future

The Future of News: A Challenge to Both Sides of the House

Rick Edmonds, Poynter Researcher and Writer: “A bright future for newspapers depends on two things that may sound the same but are actually different:

(1) Editors and newsroom staff must continue as the primary news providers in their communities, adapting and delivering reports on multiple platforms, innovating in form, voice, variety and audience-focused content.

(2) As businesses, newspapers must generate new sources of income as traditional ones fade. That includes online display advertising, rich and competitive local classified, local search, other online income and multiple niche publications. They must also get the best results — discovering new lines of business and holding on to the old — in the paper edition.”

Soft Bath is a soft cushioned bathtub made from special materials. It’s simple: furniture and baths meant for comfort should be soft. Your couch and bed are already soft, and from now on your bathtub will be soft and comfortable!

The Soft Bath is one integrated product with three layers. There is a framework from fibreglass, then a soft layer and ultimately the strong and flexible top coating. This material is strong, robust, and stays flexible. Soft Bath looks exactly like a conventional hard bath and is as easy to install.

Next Event: Wednesday, June 28, 16:30-19:15

the future of Journalism – Ethics in Journalism

When: Wednesday, June 28, 2006, 16:00-19:15

Where: PricewaterhouseCoopers, Thomas R. Malthusstraat 5, 1066 JR Amsterdam

Milverton Wallace, founder/organiser of the European Online Journalism Awards

The new Corinthians versus the standard-bearers: How the web is socialising journalism ethics

Guy Thornton, Chair, Netherlands NUJ Branch

Does and should journalism have boundaries and if so where and how should they be drawn?

Neville Hobson, Accredited Communication Practitioner, ABC

The age of gatekeeper journalism is over

Homme Heida, Promedia, Member of the Club of Amsterdam Round Table

Summit for the Future blog

| Summit for the Future blog http://summitforthefuture.blogspot.com July 13: Summary of the Summit for the Future 2006 May 22: Dispatches from the Frontier |

Recommended Book

The Vanishing Newspaper: Saving Journalism In The Information Age

by Philip Meyer

For more than thirty years the newspaper industry has been losing readers at a slow but steady rate. News professionals are inclined to blame themselves, but the real culprit is technology and its competing demands on the public’s time. The Internet is just the latest in a long series of new information technologies that have scattered the mass audience that newspapers once held. By isolating and describing the factors that made journalism work as a business in the past, Meyer provides a model that will make it work with the changing technologies of the present and future. He backs his argument with empirical evidence, supporting key points with statistical assessments of the quality and influence of the journalist’s product, as well as its effects on business success.

If Thailand is ‘New Spain’ – is then South East Asia ‘New Europe’?

If Thailand is ‘New Spain’ – is then South East Asia ‘New Europe’?

by Leif Thomas Olsen. Thailand

Assistant Professor International Relations, Rushmore University

In this article I will argue that Europe needs ASEAN. I will also argue that Europeans need to learn more about the societies sitting right between two future economic giants – China and India. I will finally suggest that those of us who view the Club of Amsterdam as an interesting initiative and point of exchange should try to do something about it.

I will start by answering my own question. No, South East Asia never was, nor will it ever be, a New Europe. But it will be – which is the reason for asking this question – a threat to Europe’s crucial status as the closest ally to the world’s leading economy, the very same day that today’s leading economy is no longer supreme.

Let me clarify this. No need to mention can Europe rest assure it will enjoy a favorable treatment by the rest of the world as long as the US is the world’s sole superpower. No doubt is the US also as dependent on European support in its role as a superpower as Europe is dependent on the US in its role as its staunchest ally. Without any superpower to support, Europe would be left to its endless internal bickering without anybody taking notice. On the same token could the US never form its so called international alliances without European support, and Europe would have virtually no role at all to play in the political power struggle if it did not piggyback on US’ economic and military supremacy.

Seen from a western viewpoint this may seem as a good deal. You scratch my back and I scratch yours, even if it involves secret prisoners en route to secrets prisons (in breach of the international law these very states have agreed on), or being pushed to include US’ appointed buffer state and gatekeeper towards the Muslim world into the European Union. Making Turkey a full EU member is almost like making Mexico USA’s 51st state. Although it is probably technically possible, it is neither necessary nor likely to resolve any current issues of concern without opening up many more of far greater complexity. Full-hearted trade agreements and more generous rules for cross-border employment would be both easier to achieve and more culturally astute – unless the concept of nation states was dropped altogether by those still holding it dear.

So what about Thailand and Spain? After Spain became a highly successful EU member state has its status as Europe’s pet holiday destination in general – and pet holiday home investment destination in particular – started to decline. The Euro simply made it too expensive. The strongest candidate to gain from Spain’s drop in this field is Thailand. Some prefer Brazil, some prefer South Africa, but in terms of sheer numbers is Thailand taking the lead. So what is so good about Thailand, and what does it have to do with Europe’s role vis-à-vis the US?

Thailand markets itself as the ‘Country of Smiles’. For being a marketing slogan it comes exceptionally close to the truth. Although most westerners may not understand why they smile, is it still very pleasant with a society where one can meet so many smiling faces. (Some research even suggests that laugh-therapy can help fight cancer.) Thai people smile – like many other Asians – for all kinds of reasons. In fact, even embarrassment could be one. But they mainly smile because they have no reason not to. ‘Sabai’ and ‘sanuk’ are two key words in Thai society. Sabai means something like a combination of ‘peaceful’, ‘pleasant’ and ‘comfortable’, while sanuk simply means ‘fun’. Combining these two concepts into a ‘lifestyle’ is something most Europeans have little experience of, since responsibility, efficiency and profitability are the concepts running their everyday lives. There is a whole catalogue of reasons for why most foreigners coming to Thailand tend to enjoy it so much. One is that foreigners as such are not disliked. Thailand have had quite an open attitude towards foreigners for most of its history, and only one of Thailand’s past kings did deliberately reduce contact with them – and that was after he saw what the British did to China during the Opium War.

The number of foreign property investors buying holiday homes in Thailand is stunning. When the wealthy post WW2 baby-boom generation of the1940’s plans for a comfortable retirement life – no matter how influential they have been in shaping their own societies – do many of them look for something entirely different. It is not only the weather and the lower cost levels (which also e.g. Kenya and Brazil can offer), but also the fact that they are treated well, crime levels are (with most international standards) low, and that the way and pace of life is far more humane here than in the profit-obsessed West.

Thailand is however also a regional powerhouse. Its economic growth is as impressive as any ‘tiger’, and its role in regional politics (both past and present) cannot be missed by anyone interested in these issues. Thailand is however nowadays a part of ASEAN, a much more loosely formed grouping than EU. Although EU treats Thailand and ASEAN as countryside cousins when discussing multilateral issues, EU should, instead, be very aware of the fact that ASEAN – which started as a strict anti-communist grouping eager to stand up against influences from Mao’s China and Ho Chi Minh’s Vietnam – during the second half of the 1990’s invited, negotiated and integrated their former adversaries Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia (together with still problematic Myanmar) into its fold. If Europe is at all interested to look beyond its own nose it could here find an excellent case study for how to integrate countries like Bulgaria and Rumania into EU. But are Europe’s eyes good enough to look that far, or is Europe once again proving itself an old man – this time through its poor eyesight?

Thailand is, interestingly enough, a society that appeals to westerners when they come here as individuals, but draws criticism when the very same westerners try to figure out how to streamline Thailand into yet another global sibling – from which western styled logic and efficiency is expected. But is not the irony in all this that Thailand would risk to lose exactly those attractive features that westerners enjoy so much when coming here as individuals, if it actually did streamline itself into that global sibling that their critics wish them to ‘develop’? Is not the underlying question more about which is better; a society that is good on paper (albeit not perfect, as no society is ‘perfect’), or a society that is good for its inhabitants? Is it perhaps not so that it is Europe that has painted itself into a corner, from which it cannot escape without help? And if that is the case, could Thailand and its South East Asian neighbors in any way help Europe out of there?

If Europe and the US are inter-dependent for their current roles in the global family, isn’t it likely that China and ASEAN will develop a similar inter-dependence, once China is established as far more than just a potential economic superpower? Many signs suggest so, not the least the success of the “ASEAN+3” talks, which China (together with Japan and Korea) used to boost the importance of ASEAN, in order to reduce fear of unhealthy dominance among the far smaller ASEAN economies’ governments. If it is so, would not ASEAN’s future position vis-à-vis China become similar to Europe’s current position vis-à-vis the US? And if this is the case, how can Europe assume that they can retain any particular say in the world’s future power structures unless they get a pair of new glasses and look beyond the ordinary?

At Club of Amsterdam’s recent ‘Summit for the Future’ did many speakers point towards Asia. But the target was mainly China and India. Britain may feel nostalgic about India, and wish this is being returned, but in reality is modern India looking towards the US – not Europe – for economic and political clout, with which it hopes it may one day become capable of competing with China. Europe should therefore nurture closer links to South East Asia, in the short term to learn more about these truly dynamic societies, in the longer term to secure a back door to the world’s future economic giants in general – and China in particular.

The Club of Amsterdam (and its active as well as less active members) could help this by supporting the setting up of a Club of Bangkok. By helping to establish its own sister in the most important hub in South East Asia, it would get a direct inroad in to the region, and quickly gain real-term understanding of how these fast-growing societies think and behave, instead of relying on off-the-shelf analysis that large multinational consultancies issue, using their ‘easy-to-apply’ pre-packaged world views where only big is beautiful.

The Statu(t)e of Liberty. Spatial Location as a Blueprint of Evil

| The Statu(t)e of Liberty. Spatial Location as a Blueprint of Evil by Markus Miessen, architect, researcher and writer teaching at the Architectural Association |

“The United States became engaged in two distinct conflicts, Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) in Afghanistan and Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) in Iraq. As a result of a Presidential determination, the Geneva Conventions did not apply to al Quaeda and Taliban combatants.” (1) – Schlesinger Report |

The present re-read

Analysing the relationship between space and power, many questions arise about how far spatial conditions have influenced and continue to affect conscious violations of Human Rights. A few years into the 21st century, decreasing public confidence in political decision-making and its transfer has made way for an overbearing universal ethics of mediated truisms. Post 9/11 in particular, one can trace an increasing habit of politicians to convert the mis-en-scene and tools of spatial planning in order to create microclimates, which do not obey any legal framework. There is evidence that spatial planning has been used as a mechanism to convert spaces into strategic weapons of physical punishment. Simultaneously, one is witnessing the re-appropriation of issues such as representation, psychological framework and an increasingly monotheistic politics.

[…]

Spatial enclaves and the return of radical punishment

“Breaking chemical lights and pouring the phosphoric liquid on detainees; pouring cold water on naked detainees; beating detainees with a broom handle and a chair; threatening male detainees with rape; allowing a military police guard to stitch the wound of a detainee who was injured after being slammed against the wall in his cell; sodomizing a detainee with a chemical light (…).” (19)

Major General Antonio M. Taguba

Within this imagery, there seems to be a strong link to what Michel Foucault described as the “ceremonial of punishment” (20): “some prisoners may be condemned to be hanged, (…) others, for more serious crimes, to be broken alive and to die on the wheel, after having their limbs broken; others to be broken until they die a natural death, others to be strangled and then broken, others to be burnt alive, (…) and others to have their heads broken.” (21) In Discipline & Punish, The Birth of the Prison, Foucault illustrates in how far physical punishment has become the most hidden part of the penal process and “as a result, justice no longer takes public responsibility for the violence that is bound up with its practice.” (22) As opposed to historic reference, in the 20th century – he argues – the spectacle of punishment has shifted to the trial. But if there is no trial, there is no scene. The disappearance of public punishment goes hand in hand with the decline of spectacle. Commenting on space and power, Paul Hirst subsequently defined such politics as “a much contested concept: it has many different meanings and possible spatial locations.” (23) Foucault’s treatment of the relation between a new form of power and a new class of specialist structures regarded this both as the consequence and the condition of the rise of forms of “disciplinary power” from the 18th century onwards: “power is thus conceived of a fundamentally negative, as a punitive relation between the dominant and the subordinate subject.” (24) This form of power based on surveillance, which individuates and transforms, is defined by the penitentiary prison with its cells spatially isolating its inmates, with a central structure of inspection. What Hirst describes as the essential characteristics of Bentham’s Panopticon – “an idea in architecture” (25) – that is to say the principle that the many can be governed by the few, can be traced through the history of penitentiary construction. This is probably best exemplified by Abu Ghuraib’s “Liberty Tower”, a central inspection structure overlooking the territory: a space that enables both a certain correlative perspective and power relations. Although Foucault’s writings on the Panopticon originate from the 1970’s, his work seems more relevant than ever. He dissects the relationship between space and power.

In order to illustrate the effect of institutional space and its power-relations, Philip Zimbardo – professor emeritus at Stanford University – carried out an experiment in 1971 to test a simple question: what happens if you put “good” people in an “evil space”? To run the experiment, student volunteers were randomly assigned to plan the role of prisoner or guard in a simulated prison. Although all participants had been examined and were confirmed to be mentally healthy, guards soon became sadistic and prisoners showed severe signs of depression. After six days, the study had to be stopped in order to prevent further abuse. The experiment clarified how the power of social and spatial constructs distorts personal identities and values as students had internalised situated identities in their roles as prisoners and guards. When Zimbardo gave an interview to the Edge Foundation in 2005, he argued that “understanding the abuses at this Iraqi prison starts with an analysis of both the situational and systematic forces operating on those soldiers working the night shift in that little shop of horrors.” (26) According to Zimbardo, his experiment illustrated the competition between institutional powers versus the individual’s will to resist. Control through humiliation provided regular occasions for the guards to exercise control over the prisoners, illustrating that the relationship between pleasure and pain, in a territory that is spatially independent and functioning under its own set of rules, is no longer based on a framework of human reasoning.

[…] Both Guantanamo and Abu Ghuraib are a showcase in the failure of ethical planning and a manifesto of the powerful, creating a blend of physical and non-physical components that create an overall fabric of control-space. The question therefore needs to be: do we need a Geneva Convention for the built environment, a court of justice to persecute spatial war crimes?

Somewhere between the flood of Human Rights documents, the Stanford Prison Experiment, Zacarias De La Rocha’s “is all the world jails and churches?” (34) and Salman Rushdie’s claim that “we need more teachers and fewer priests in our lives” (35), one starts to trace the failure and bitterness of geopolitics. But zooming out of the spatial enclaves, there is hope: breaking the stoic narrative that suggests the return to preenlightened vision, resisting the re-introduction of moral truisms, turning inside-out the model of the world in which religion is part of the public realm, the answer – on a larger scale – can only be the return to secular politics.

This text is a short extract from an essay to be published in the forthcoming book “5 Codes – Architecture in the Age of Fear and Terror” (Birkhäuser – Basel / Boston / Berlin).

Markus Miessen is an architect, researcher and writer teaching at the Architectural Association. He is the co-author of “Spaces of Uncertainty” (Mueller & Busmann, 2002) and currently acts as a spatial consultant to the European Kunsthalle Cologne. His forthcoming publication “Did someone Say Participate? An Atlas of Spatial Practice” (MIT Press/ Revolver, co-edited by Shumon Basar) will be published in June.

Architectural Body Research Foundation

Architectural Body Research Foundation

| Since 1963, artists-architects-poets Arakawa and Madeline Gins have worked in collaboration to produce visionary, boundary-defying art and architecture. Their seminal work, The Mechanism of Meaning, has been exhibited widely throughout the world. In 1987, as a means of financing the design and construction of works of procedural architecture that draw on The Mechanism of Meaning, extending its theoretical implications into the environment, Arakawa and Gins founded the Architectural Body Research Foundation. The Foundation actively collaborates with leading practitioners in a wide-range of disciplines including, but not limited to, experimental biology, neuroscience, quantum physics, experimental phenomenology, and medicine. Architectural projects have included residences (Reversible Destiny Houses, Bioscleave House, Shidami Resource Recycling Model House), parks (Site of Reversible Destiny-Yoro) and plans for housing complexes and neighborhoods (Isle of Reversible Destiny-Venice and Isle of Reversible Destiny-Fukuoka, Sensorium City, Tokyo). |

| Reversible Destiny Lofts – Mitaka |

Agenda

June 28

..the future of Journalism

.Ethics in Journalism

Where: PricewaterhouseCoopers, Thomas R. Malthusstraat 5, 1066 JR Amsterdam

Club of Amsterdam Open Business Club

| Club of Amsterdam Open Business Club Are you interested in networking, sharing visions, ideas about your future, the future of your industry, society, discussing issues, which are relevant for yourself as well as for the ‘global’ community? The future starts now – join our online platform … |

Customer Reviews

Thanks for submitting your comment!