Content

Welcome to the Club of Amsterdam Journal.

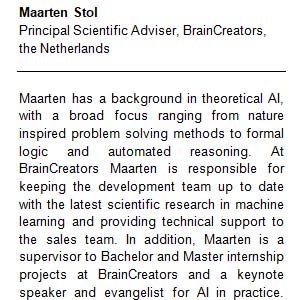

The Future Now Show about AI and Business with Maarten Stol

“Artificial Intelligence hype and showcases the real business value that’s already emerging from AI applications across sectors. Maarten shares real life insights.”

Felix B Bopp, Founder & Chairman

We talk about artistic inspiration all the time – but scientific inspiration is a thing too

By Tom McLeish, Professor of Natural Philosophy in the Department of Physics, University of York

I don’t know why it took so long to dawn on me – after 20 years of a scientific career – that what we call the “scientific method” really only refers the second half of any scientific story. It describes how we test and refine the ideas and hypotheses we have about nature through the engagement of experiment or observation and theoretical ideas and models.

But something must happen before this. All of this process rests upon the vital, essential, precious ability to conceive of those ideas in the first place. And, sadly, we talk very little about this creative core of science: the imagining of what the unseen structures in the world might be like.

We need to be more open about it. I have been repeatedly saddened by hearing from school students that they were put off science “because there seemed no room there for my own creativity”. What on earth have we done to leave this formulaic impression of how science works?

Science and poetry

The 20th century biologist Peter Medawar was one of the few recent writers to discuss the role of creativity in science at all. He claimed that we are quietly embarrassed about it, because the imaginative phase of science possesses no “method” at all. In his 1982 book Pluto’s Republic he points out:

The weakness of the hypothetico-deductive system, in so far as it might profess to cover a complete account of the scientific process, lies in its disclaiming any power to explain how hypotheses come into being.

Medawar is equally critical of glib comparisons of scientific creativity to the sources of artistic inspiration. Because whereas the sources of artistic inspiration are often communicated – they “travel” – scientific creativity is very much private. Scientists, he claims, unlike artists, do not share their tentative imaginings or inspired moments, but only the polished results of complete investigations.

The romantic poet William Wordsworth, on the other hand, two centuries ago, foresaw a future in which:

The remotest discoveries of the Chemist, the Botanist, or Mineralogist, will be as proper objects of the Poet’s art as any upon which it can be employed, if the time should ever come when these things shall be familiar to us.

Here is the need for ideas to “travel” again – which, if Medawar is correct, they have still failed to do. By and large poets still don’t write about science (with some notable exceptions such as R S Thomas). Nor is science “an object of contemplation”, as the historian Jacques Barzun put it. Yet the few scientists who have vocalised their experience of formulating new ideas are in no doubt about its contemplative and creative essence. Einstein, in his book with the physicist Leopold Infeld, The Evolution of Physics, wrote:

I am enough of an artist to draw freely upon my imagination. Imagination is more important than knowledge. Knowledge is limited. Imagination encircles the world.

You don’t need to be a great scientist to know this. In my own experience I have seen mathematical solutions in dreams (one dream of a mathematical solution even coming to me and independently and identically to a collaborator on the same night), and imagined a specific structure of protein dynamics while sitting on a hillside.

There is a large literature on “creativity” in science, but I have found nothing that really speaks to the lack of discussion of scientific inspiration today or to the pain of lingering experiences in education that set sciences and the arts and humanities in conflicting and opposed camps.

Stories of creativity

So I set off to ask scientists I knew to narrate, not just their research findings, but the pathways by which they got there. As a sort of “control experiment”, I did the same with poets, composers and artists.

I read past accounts of creation in mathematics (Poincaré is very good), novel-writing (Henry James wrote a book about it), art (from Picasso to my Yorkshire friend, the artist late Graeme Willson), and participated in a two day workshop in Cambridge on creativity with physicists and cosmologists. Philosophy, from medieval to 20th century phenomenology, has quite a lot to add.

From all these tales emerged a different way to think about what science achieves and where it lies in our long human story – as not only a route to knowledge, but also as a contemplative practice that meets a human need, in ways complementary to art or music. Above all I could not deny the extraordinary way that personal stories of creating the new mapped closely onto each other, whether these sprung from an attempt to create a series of mixed-media artworks reflecting the sufferings of war, or the desire to know what astronomical event had unleashed unprecedented X-ray and radio signals.

A common narrative contour of a glimpsed and desired end, a struggle to achieve it, the experience of constraint and dead-end, and even the mysterious “aha” moments that speak of hidden and sub-conscious processes of thought choosing their moments to communicate into our consciousness – all this is a story shared among scientists and artists alike.

In my resulting book – The Poetry and Music of Science – I try to make sense of why science’s imaginative and creative core is so hidden, and how to bring it into the light. It’s not the book I first imagined – it just wouldn’t permit a structure of separate accounts of scientific and artistic creativity. Their entanglements run too deep for that.

Instead there emerged three “modes” of imagination that both science and art engage: the visual, the textual and the abstract. We think in pictures, in words, and in the abstract forms that we call mathematics and music. It has become increasingly obvious to me that the “two cultures” division between the humanities and sciences is an artificial invention of the late 19th century. Perhaps the best way to address this is simply to ignore it, and start talking to one another more.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

The EU in 2018

Find out everything you need to know about the European Union’s achievements in 2018.

The General Report on the Activities of the European Union brings you up to date on how the EU is delivering on its 10 priorities, including actions to boost jobs and the economy.

Learn too about how the EU is creating a Digital Single Market to benefit citizens, is leading the fight against climate change, and agreeing new trade deals with major partners like Japan.You can find information on these and many more issues in “The EU in 2018”

The Future Now Show

Shape the future now, where near-future impact counts and visions and strategies for preferred futures start. – Club of Amsterdam

Do we rise above global challenges? Or do we succumb to them? The Future Now Show explores how we can shape our future now – where near-future impact counts. We showcase strategies and solutions that create futures that work.

Every month we roam through current events, discoveries, and challenges – sparking discussion about the connection between today and the futures we’re making – and what we need, from strategy to vision – to make the best ones.

April 2019

with

Maarten Stol

Artificial Intelligence hype and showcases the real business value that’s already emerging from AI applications across sectors. Maarten shares real life insights

The Future Now Show

Credits

Maarten Stol, Principal Scientific Adviser, BrainCreators, the Netherlands www.braincreators.com

A Technology to Reverse Climate Change

Climeworks captures CO2 from air with the world’s first commercial carbon removal technology. Our direct air capture plants remove CO2 from the atmosphere to supply to customers and to unlock a negative emissions future.

WHAT IS CARBON DIOXIDE REMOVAL AND WHY IS IT IMPORTANT?

Climate change is driven by human activities such as burning fossil fuels, which release carbon dioxide into the air, causing global warming.

The 2016 Paris Agreement aims to keep the increase in the global average temperature to “well below” 2 °C above pre-industrial levels, in order to significantly reduce the risks and impacts of climate change on the planet.

Although significant strides have been made in renewable energy and energy efficiency, these are not enough to meet the critical 2 °C target. Additional CO2 removal from the atmosphere will be required.

Climate change mitigation therefore urgently needs carbon removal technologies. Eighty seven per cent of all IPCC climate scenarios make it clear that negative emissions are absolutely necessary in order to keep global warming below 2 °C.

Importantly CO2 removal is not only needed to enable negative emissions but also to achieve zero CO2 emissions globally. Sectors such as shipping and aviation do not yet have viable alternatives to fossil fuels. Traditional mitigation measures such as renewable energies can – even in the optimum scenario – only reduce CO2 by around 80 per cent. The rest must come from removing carbon from the air.

Climeworks has developed the first commercial carbon removal technology on the market today, allowing us to physically remove any organisation’s or individual’s past, present and future CO2 emissions.

Our plants capture atmospheric carbon with a filter. Air is drawn into the plant and the CO2 within the air is chemically bound to the filter.

Once the filter is saturated with CO2 it is heated (using mainly low-grade heat as an energy source) to around 100 °C (212 °F). The CO2 is then released from the filter and collected as concentrated CO2 gas to supply to customers or for negative emissions technologies.

CO2-free air is released back into the atmosphere. This continuous cycle is then ready to start again. The filter is reused many times and lasts for several thousand cycles.

A Technology to Reverse Climate Change

News about the Future

The Animal-AI Olympics

We are proposing a new kind of AI competition. Instead of providing a specific task, we will provide a well-defined arena and a list of cognitive abilities that we will test for in that arena. Many elements will be fixed and known in advance. The tests will all use the same agent with the same inputs and actions. The goal will always be to retrieve the same food items by interacting with previously seen objects. However, the exact layout and variations of the tests will not be released until after the competition.

We expect this to be hard challenge. Winning this competition will require an AI system that can behave robustly and generalise to unseen cases. A perfect score will require a breakthrough in AI, well beyond current capabilities. However, even small successes will show that it is possible, not just to find useful patterns in data, but to extrapolate from these to an understanding of how the world works.

The Future of Urban Living

Foresight Research paper produced from a Think-Tank consultation held at St George’s House, Windsor Castle in December 2018.

This foresight research paper was produced from a Think-Tank consultation that explored the ‘Future of Urban Living’ in 2040. The consultation was organised by Future iQ, in conjunction with St George’s House at Windsor Castle, United Kingdom. It was held on 13-14 December 2018. People from various backgrounds and professions participated and developed the topics and scenarios presented in this report. The consultation focussed its discussions on the future of urban living, primarily in the context of cities in the more developed countries of the world. It is recognised that significant portions of the global urban population will reside in cities in developing counties, and that in some cases, those cities will have different challenges and outcomes.

A Better Path to Prosperity

Umair Haque, author of “The New Capitalist Manifesto“, explains how companies can create real, lasting value.

Recommended Book

The Age of Surveillance Capitalism by Shoshana Zuboff

by Shoshana Zuboff

The challenges to humanity posed by the digital future, the first detailed examination of the unprecedented form of power called “surveillance capitalism,” and the quest by powerful corporations to predict and control our behavior.

In this masterwork of original thinking and research, Shoshana Zuboff provides startling insights into the phenomenon that she has named surveillance capitalism. The stakes could not be higher: a global architecture of behavior modification threatens human nature in the twenty-first century just as industrial capitalism disfigured the natural world in the twentieth.

Zuboff vividly brings to life the consequences as surveillance capitalism advances from Silicon Valley into every economic sector. Vast wealth and power are accumulated in ominous new “behavioral futures markets,” where predictions about our behavior are bought and sold, and the production of goods and services is subordinated to a new “means of behavioral modification.”

The threat has shifted from a totalitarian Big Brother state to a ubiquitous digital architecture: a “Big Other” operating in the interests of surveillance capital. Here is the crucible of an unprecedented form of power marked by extreme concentrations of knowledge and free from democratic oversight. Zuboff’s comprehensive and moving analysis lays bare the threats to twenty-first century society: a controlled “hive” of total connection that seduces with promises of total certainty for maximum profit – at the expense of democracy, freedom, and our human future.

With little resistance from law or society, surveillance capitalism is on the verge of dominating the social order and shaping the digital future – if we let it.

Illuminate a flower

It all starts in 2016 with an idea : how to illuminate a flower ? After several months of tests and experimentations, the serum allowing any cutflowers to glow was created together with the company Design Aglaé, the first luminescent vegetal design agency.

Our next goal, which will be realized by the end of the year, is flower stabilization : which allows them to everlast (at least several years) and emit light without any maintenance. These products will be used sustainably for different spaces such as hotels, company places and restaurant chains.

Our ambition for 2020 ?

Currently, we are working on a specific type of light which doesn’t need any electrical source : it is called vegetal phosphorescence. Its involves storing the daylight and release it at night.

Our ambition is to design soft plant light solutions, in order to replace some electrical lighting sources

Our commitment is to favor the lighting and greening of the cities and to allow the rural areas less enlightened for economic reasons to use this technology. Roadside, parks and gardens, landscaping … and even some remote areas of the Third World, who do not have access to electricity..

Brightened plants without outside light sources, in order to illuminate cities… thanks to the glow of trees !

Luminescence

Thanks to a unique serum, your flowers will wear a magical luminescent effect so you may enjoy them by night !

The effect is visible on petals and leaves.

Conservation

No more flowers that fade too quickly. The Aglaé biodegradable nutrient prolongs the life of your flowers and allows you to enjoy them longer !

Design

The sleek and elegant design of our black light soliflore is an original object that will dress your interior poetically.

Urban Resilience

100 Resilient Cities helps cities around the world become more resilient to social, economic, and physical challenges that are a growing part of the 21stcentury. 100RC provides this assistance through: funding for a Chief Resilience Officer in each of our cities who will lead the resilience efforts; resources for drafting a resilience strategy; access to private sector, public sector, academic, and NGO resilience tools; and membership in a global network of peer cities to share best practices and challenges.

What is Urban Resilience?

Futurist Portrait: Judith L. Hand

Judith L. Hand is an evolutionary biologist, animal behaviorist, novelist, futurist and pioneer in the emerging field of peace ethology. She writes on a variety of topics related to ethology, including the biological and evolutionary roots of war, gender differences in conflict resolution, empowering women, and abolishing war. Her lectures include recent developments in peace research, which may help us prevent war. Her book, Women, Power, and the Biology of Peace is an in-depth exploration of human gender differences with regard to aggression.

“Because of genetic inclinations that are as deeply rooted as the bonding-for-aggression inclinations of men, most women would prefer to make or keep the peace, the sooner the better.” In Women, Power, and the Biology of Peace.

“If women around the world in the twenty-first century would get their act together they could, partnered with men of like mind, shift the direction of world history to create a future without war.” In A Future Without War: the Strategy of a Warfare Transition.

Why Can’t a Woman be More Like a Man?

Customer Reviews

Thanks for submitting your comment!