Content

Welcome to the Club of Amsterdam Journal.

The Future Now Show featuring We Make Change with James Sancton hosted by Annie Moon

“James Sancto and his team at We Make Change are rewriting the way in which volunteering and social change takes place. We Make Change, is not just a platform, it’s a movement. Millennials, the generation of digital natives, with access to connectivity and immense technological innovation, are the first generation with the potential to address global poverty and the last with the opportunity to stop climate change.”

Felix B Bopp, Founder & Chairman

We’re not prepared for the genetic revolution that’s coming

By Robert Chapman, PhD Candidate,Goldsmiths, University of London

When humans’ genetic information (known as the genome) was mapped 15 years ago, it promised to change the world. Optimists anticipated an era in which all genetic diseases would be eradicated. Pessimists feared widespread genetic discrimination. Neither of these hopes and fears have been realised.

The reason for this is simple: our genome is complex. Being able to locate specific differences in the genome is only a very small part of understanding how these genetic variants actually work to produce the traits we see. Unfortunately, few people understand just how complex genetic

s really is. And as more and more products and services start to use genetic data, there’s a danger that this lack of understanding could lead people to make some very bad decisions.

At school we are taught that there is a dominant gene for brown eyes and a recessive one for blue. In reality, there are almost no human traits that are passed from generation to generation in such a straightforward way. Most traits, eye colour included, develop under the influence of several genes, each with its own small effect.

What’s more, each gene contributes to many different traits, a concept called pleiotropy. For example, genetic variants associated with autism have also been linked with schizophrenia. When a gene relates to one trait in a positive way (producing a healthy heart, say) but another in a negative way (perhaps increasing the risk of macular degeneration in the eye), it is known as antagonistic pleiotropy.

As computing power has increased, scientists have been able to link many individual molecular differences in DNA with specific human characteristics, including behavioural traits such as educational attainment and psychopathy. Each of these genetic variants only explains a tiny amount of variation in a population. But when all these variants are summed together (giving what’s known as a characteristic’s polygenic score) they begin to explain more and more of the differences we see in the people around us. And with a lack of genetic knowledge, that’s where things start to be misunderstood.

For example, we could sequence the DNA of a newborn child, calculate their polygenic score for academic achievement and use it to predict, with some degree of accuracy, how well they will do in school. Genetic information may be the strongest and most precise predictor of a child’s strengths and weaknesses. Using genetic data could allow us to more effectively personalise education and target resources to those children most in need.

But this would only work if parents, teachers and policymakers have enough understanding of genetics to correctly use the information. Genetic effects can be prevented or enhanced by changing a person’s environment, including by providing educational opportunity and choice. The misplaced view that genetic influences are fixed could lead to a system in which children are permanently separated into grades based on their DNA and not given the right support for their actual abilities.

Better medical knowledge

In a medical context, people are likely to be given advice and guidance about genetics by a doctor or other professional. But even with such help, people who have better genetic knowledge will benefit more and will be able to make more informed decisions about their own health, family planning, and health of their relatives. People are already confronted with offers to undergo costly genetic testing and gene-based treatments for cancer. Understanding genetics could help them avoid pursuing treatments that aren’t actually suitable in their case.

It is now possible to edit the human genome directly using a technique called CRISPR. Even though such genetic modification techniques are regulated, the relative simplicity of CRISPR means that biohackers are already using it to edit their own genomes, for example, to enhance muscle tissue or treat HIV.

Such biohacking services are very likely to be made available to buy (even if illegally). But as we know from our explanation of pleiotropy, changing one gene in a positive way could also have catastrophic unintended consequences. Even a broad understanding of this could save would-be biohackers from making a very costly and even potentially fatal mistake.

When we don’t have medical professionals to guide us, we become even more vulnerable to potential genetic misinformation. For example, Marmite recently ran an ad campaign offering a genetic test to see if you either love or hate Marmite, at a cost of £89.99. While witty and whimsical, this campaign also has several problems.

First, Marmite preference, just like any complex trait, is influenced by complex interactions between genes and environments and is far from determined at birth. At best, a test like this can only say that you are more likely to like Marmite, and it will have a great deal of error in that prediction.

Second, the ad campaign shows a young man seemingly “coming out” to his father as a Marmite lover. This apparent analogy to sexual orientation could arguably perpetuate the outdated and dangerous notion of “the gay gene”, or indeed the idea that there is any single gene for complex traits. Having a good level of genetic knowledge will enable people to better question advertising and media campaigns, and potentially save them from wasting their money.

My own research has shown that even the well-educated amongst us have poor genetic knowledge. People are not empowered to make informed decisions or to engage in fair and productive public discussions and to make their voices heard. Accurate information about genetics needs to be widely available and more routinely taught. In particular, it needs to be incorporated into the training of teachers, lawyers and health care professionals who will very soon be faced with genetic information in their day-to-day work.

To test your genetic knowledge and see how ready you are to make informed decisions in the genomic era visit The International Genetics Literacy and Attitudes Survey and contribute to our ongoing research.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license

Arm-a-Dine

exercion games lab developed Arm-a-Dine, a social eating system that uses an on-body third arm to explore augmented eating experiences. Arm-a-Dine is a novel interactive multiplayer experience where a third (robotic) arm attached to the stomach of the person supports his/her eating, in particular, we sense facial expressions of other co-eaters to guide the actions of the third arm, fuelling the interlink between eating and facial expressions. With our work, we aim to explore the potential of embodied systems to support the social eating experience.

The Future Now Show

Shape the future now, where near-future impact counts and visions and strategies for preferred futures start. – Club of Amsterdam

Do we rise above global challenges? Or do we succumb to them? The Future Now Show explores how we can shape our future now – where near-future impact counts. We showcase strategies and solutions that create futures that work.

Every month we roam through current events, discoveries, and challenges – sparking discussion about the connection between today and the futures we’re making – and what we need, from strategy to vision – to make the best ones.

December 2018 / January 2019

with

James Sancton

hosted by

Annie Moon

“James Sancto and his team at We Make Change are rewriting the way in which volunteering and social change takes place. We Make Change, is not just a platform, it’s a movement. Millennials, the generation of digital natives, with access to connectivity and immense technological innovation, are the first generation with the potential to address global poverty and the last with the opportunity to stop climate change.”

The Future Now Show

Credits

James Sancto, Co-Founder & CEO, lWe Make Change

Annie Moon, Host, Be the Difference, When good stuff happens, virtual conference

www.bethedifferenceva.com

Repair Café

Repair Cafés are free meeting places and they’re all about repairing things (together). In the place where a Repair Café is located, you’ll find tools and materials to help you make any repairs you need. On clothes, furniture, electrical appliances, bicycles, crockery, appliances, toys, et cetera. You’ll also find expert volunteers, with repair skills in all kinds of fields.

Visitors bring their broken items from home. Together with the specialists they start making their repairs in the Repair Café. It’s an ongoing learning process. If you have nothing to repair, you can enjoy a cup of tea or coffee. Or you can lend a hand with someone else’s repair job. You can also get inspired at the reading table – by leafing through books on repairs and DIY.

There are over 1.500 Repair Cafés worldwide. Visit one in your area or start one yourself!

We throw away vast amounts of stuff. Even things with almost nothing wrong, and which could get a new lease on life after a simple repair. The trouble is, lots of people have forgotten that they can repair things themselves or they no longer know how. Knowing how to make repairs is a skill quickly lost. Society doesn’t always show much appreciation for the people who still have this practical knowledge, and against their will they are often left standing on the sidelines. Their experience is never used, or hardly ever.The Repair Café changes all that! People who might otherwise be sidelined are getting involved again. Valuable practical knowledge is getting passed on. Things are being used for longer and don’t have to be thrown away. This reduces the volume of raw materials and energy needed to make new products. It cuts CO2 emissions, for example, because manufacturing new products and recycling old ones causes CO2 to be released.The Repair Café teaches people to see their possessions in a new light. And, once again, to appreciate their value. The Repair Café helps change people’s mindset. This is essential to kindle people’s enthusiasm for a sustainable society.But most of all, the Repair Café just wants to show how much fun repairing things can be, and how easy it often is. Why don’t you give it a go?

News about the Future

Putting food-safety detection in the hands of consumers

MIT Media Lab researchers have developed a wireless system that leverages the cheap RFID tags already on hundreds of billions of products to sense potential food contamination.

Food safety incidents have made headlines around the globe for causing illness and death nearly every year for the past two decades. Back in 2008, for instance, 50,000 babies in China were hospitalized after eating infant formula adulterated with melamine, an organic compound used to make plastics, which is toxic in high concentrations. And this April, more than 100 people in Indonesia died from drinking alcohol contaminated, in part, with methanol, a toxic alcohol commonly used to dilute liquor for sale in black markets around the world.

The researchers’ system, called RFIQ, includes a reader that senses minute changes in wireless signals emitted from RFID tags when the signals interact with food. For this study they focused on baby formula and alcohol, but in the future, consumers might have their own reader and software to conduct food-safety sensing before buying virtually any product. Systems could also be implemented in supermarket back rooms or in smart fridges to continuously ping an RFID tag to automatically detect food spoilage, the researchers say.

Climeworks

captures CO2 from air with the world’s first commercial carbon removal technology. Our direct air capture plants remove CO2 from the atmosphere to supply to customers and to unlock a negative emissions future.

Our plants capture atmospheric carbon with a filter. Air is drawn into the plant and the CO2 within the air is chemically bound to the filter.

Once the filter is saturated with CO2 it is heated (using mainly low-grade heat as an energy source) to around 100 °C (212 °F). The CO2 is then released from the filter and collected as concentrated CO2 gas to supply to customers or for negative emissions technologies.

CO2-free air is released back into the atmosphere. This continuous cycle is then ready to start again. The filter is reused many times and lasts for several thousand cycles.

Reimagining Civilization with Floating Cities

At The Seasteading Institute, we believe that experiments are the source of all progress: to find something better, you have to try something new. But right now, there is no open space for experimenting with new societies.

That’s why we work to enable seasteading communities — floating cities — which will allow the next generation of pioneers to peacefully test new ideas for how to live together.

Our planet is suffering from serious environmental problems: coastal flooding due to severe storms caused in part by atmospheric pollution and diminishing natural resources among them. But the seas can be home to a new breed of pioneers, seasteaders, who are willing to homestead the Blue Frontier. Oil platforms and cruise ships already inhabit the waters; now it’s time to take the next step to full-fledged ocean civilizations.

Joe Quirk and Patri Friedman show us how cities built on floating platforms in the ocean will work, and they profile some of the visionaries who are implementing basic concepts of seasteading today.

Seasteading may be visionary, but it already has begun proving the adage that yesterday’s science fiction is tomorrow’s science fact.

Recommended Book

The European Union – What it is and what it does

This publication is a guide to the European Union (EU) and what it does. The first section explains in brief what the European Union is. The second section, ‘What the European Union does’, describes what the EU is doing in 35 different areas to improve the lives of people in Europe and further afield. The third section, ‘How the European Union makes decisions and takes action’, describes the institutions at the heart of the EU’s decision-making process and how their decisions are translated into actions.

A new visualization of Drive Sweden’s long-term vision

This video animation was originally created by the Drive Me project in order to build awareness among the general public about what the future will bring in terms of automated cars. It was recently updated and has now been approved by Drive Sweden’s board as a visualization of our common vision for Drive Sweden. Drive Sweden is a Strategic Innovation Program launched by the Swedish government.

Drive Sweden has developed an outlook that shows what we want to jointly achieve within our partnership until 2030.

In order to reach our vision for a connected, autonomous, and shared mobility; a number of intermediary steps are necessary. Efforts in vehicle, mobility services and transport system research will be undertaken in an integrated manner that guarantees that Sweden’s mobility of the future will be sustainable, safe, efficient, while also being attractive. In the coming years, this plan will be updated regularly as we follow up on our achievements.

UN Alliance aims to put fashion on path to sustainability

The fashion industry has seen a spectacular growth in the early 21st century. It is now valued at more than 2.5 trillion dollars and employs over 75 million people worldwide. Between 2000 and 2014, clothing production doubled with the average consumer buying 60 percent more pieces of garment compared to 15 years ago. Yet, each clothing item is now kept half as long. The industry has truly entered the era of “fast fashion”.

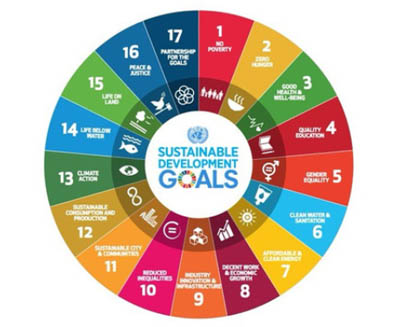

Despite an increase in jobs, this development comes at a price. The general current states of the fashion industry can be described as an environmental and social emergency. Nearly 20 percent of global waste water is produced by the fashion industry, which also emits about ten percent of global carbon emissions. In addition, the textiles industry has been identified in recent years as a major contributor to plastic entering the ocean, which is a growing concern because of the associated negative environmental and health implications. Fast fashion is also linked to dangerous working conditions due to unsafe processes and hazardous substances used in production. Costs reductions and time pressures are often imposed on all parts of the supply chain, leading to workers suffering from long working hours and low pay.The fashion industry is a $2.5 trillion-dollar industry that employs over 75 million people worldwide, most of them women. Fashion is therefore a key economic sector, which has an essential role to play in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

At the same time, fashion is an environmental and social emergency. Nearly 20 percent of global waste water is produced by the fashion industry (SDG 6), which also emits about ten percent of global carbon emissions – more than the emissions of all international flights and maritime shipping combined (SDG 13). Cotton farming is responsible for 24 percent of insecticides and 11 percent of pesticides despite using only 3 percent of the world’s arable land (SDG 3). In addition, the textiles industry has been identified in recent years as a major contributor to plastic entering the ocean (SDG 14), which is a growing concern

because of the associated negative environmental and health implications. Moreover, fast fashion is also linked to dangerous working conditions (SDG 8) due to unsafe processes and hazardous substances used in production (SDG 3). Costs reduction and time pressures are often imposed on all parts of the supply chain, leading to employees suffering from long working hours and low pay, with evidence, in some instances, of a lack of respect for fundamental principles and rights at work.

Changing consumption patterns towards sustainable behaviours and attitudes requires a shift in how we think about and value garments (SDG 12), with the goal to integrate the true costs of all the resources required for the production process and account for all environmental and social impacts.

Despite several organisations’ initiatives, there is yet no coherent, coordinated approach taken by the United Nations to address issues related to the fashion industry. In order to change this, stakeholders from different UN organisations, civil society and industry gathered at the panel event “Fashion and the SDGs: what role for the UN?”, which was organized in March 2018 in the context of the Regional Forum on Sustainable Development in the UNECE region. The panel discussed how the UN could reach a more comprehensive approach towards the development of a sustainable fashion industry in order to contribute to the achievement of the SDGs. The event was successful in establishing a clear link between the fashion industry and the SDGs, many of which will be reviewed at the UN High Level Political Forum, in particular through SDG 6 on clean water and sanitation, SDG 12 on sustainable consumption and production and SDG 15 on life on land. Recommendations discussed prior and during the event included the importance of exploring the establishment of a UN Partnership on Sustainable Fashion. Indeed, it is recognized by SDG 17 that the achievement of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development will require different actors working together.

UN Environment took a bold step in agreeing to host the Alliance during its first year, and formally launch it at their next Environment Assembly in March 2019.

Futurist Portrait: Matthew Griffin

“We’re optimists who believe that technology can be used for the good of all humanity. That’s why we want to educate and inspire people, and put them in a position to understand and use exponential technologies,” says Matthew Griffin, Founder and CEO of the 311 Institute, referring to technologies such as artificial intelligence, gene editing, nanotechnology, semiconductors, and beyond, whose power virtually doubles every year.

In Griffin’s view, for example, society has a lot of catching up to do if we are to be ready for a ubiquitously connected future in which virtually any question, even a complicated medical diagnosis, can be answered with a dense network of sensors and intelligent devices.

“As soon as students graduate from a university, their knowledge is often already outdated. It would be naive to ascribe magic powers to new technologies, but they can unlock new opportunities for tackling humanity’s great unsolved challenges, from poverty and hunger to education to health. We believe,” adds Griffin, “in a future of abundance, of energy, of food, of and of resources of all kinds, not of deprivation. And we should all help build this future for the benefit of all of us, not just one country, or the elites.”

Matthew Griffin, award winning Futurist and Founder of the 311 Institute is described as “The Adviser behind the Advisers.”

Recognised for the past five years as one of the world’s foremost futurists, innovation and strategy experts Matthew is an author, entrepreneur international speaker who helps investors, multi-nationals, regulators and sovereign governments around the world envision, build and lead the future. Today, asides from being a member of Centrica’s prestigious Technology and Innovation Committee and mentoring XPrize teams, Matthew’s accomplishments, among others, include playing the lead role in helping the world’s largest smartphone manufacturers ideate the next five generations of mobile devices, and what comes beyond, and helping the world’s largest high tech semiconductor manufacturers envision the next twenty years of intelligent machines.

Matthew’s clients include Accenture, Bain & Co, Bank of America, Blackrock, Bloomberg, Booz Allen Hamilton, Boston Consulting Group, Dell EMC, Dentons, Deloitte, Deutsche Bank, Du Pont, E&Y, Fidelity, Goldman Sachs, HPE, Huawei, JP Morgan Chase, KPMG, Lloyds Banking Group, McKinsey & Co, Monsanto, PWC, Qualcomm, Rolls Royce, SAP, Samsung, Schroeder’s, Sequoia Capital, Sopra Steria, UBS, the UK’s HM Treasury, the USAF and many others.

Futurist Keynote Speaker Matthew Griffin: Investing in the Future, Infosys Finacle, Antwerp

Wow Thanks for this posting i find it hard to locate smart important information out there when it comes to this material appreciate for the content website