Content

Practicing Commons in Community Gardens: Urban Gardening as a Corrective for Homo Economicus

Next Event: the future of Urban Gardening

Insight on Conflict

Club of Amsterdam blog

News about the Future

The EU: the third great European cultural contribution to the world

Recommended Book: The Urban Homestead: Your Guide to Self-Sufficient Living in the Heart of the City

Welcome to the Club of Amsterdam Journal.

Urban Gardening, Urban Farming or Urban Agriculture is the practice of cultivating, processing, and distributing food in or around a village, town, or city. Urban agriculture can also involve animal husbandry, aquaculture, agroforestry, and horticulture. These activities also occur in peri-urban areas as well.

Join us at our next Season Event about the future of Urban Gardening – Thursday, June 27, 18:30 – 21:15!

A collaboration with the Museum Geelvinck.

Felix F Bopp, Founder & Chairman

Practicing Commons in Community Gardens: Urban Gardening as a Corrective for Homo Economicus

By Christa Müller, sociologist and author.

An essay in the book The Wealth of the Commons: A World Beyond Market and State by David Bollier (Editor), Silke Helfrich (Editor)

“In these times of ever more blatant marketing of public space, the aspiration to plant potatoes precisely there – and without restricting entry – is nothing less than revolutionary,” writes Sabine Rohlf in her book review of Urban Gardening. (1) Indeed, we can observe the return of gardens to the city everywhere and see it as an expression of a changing relationship between the public and the private. And it is not only this dominant differentiation in modern society that is increasingly becoming blurred; the differences between nature and society as well as that between city and countryside are fading as well, at least from the perspective of urban community gardeners.

In the 1960s, as the economy boomed, people in West Germany had given up their urban vegetable gardens, not least for reasons of social status; many wished to demonstrate, for example, that they could purchase food and no longer had to grow and preserve it themselves. Today, in contrast, the “Generation Garden” has planted its feet firmly in vegetable patches in the midst of hip urban neighborhoods, the “young farmers of Berlin-Kreuzberg” are creating a furor, the German Federal Cultural Foundation stages the festival “Über Lebenskunst” (a pun meaning both “On the art of living” and – spelled Überlebenskunst – “The art of survival”) and people need not be ashamed of showing their fingernails, black from gardening, in public.

What we observe here is a shift in the symbolism and status of post-materialistic values and lifestyles. Do-it-yourself and grow-it-yourself also means finding one’s own expression in the products of one’s labor. It means setting oneself apart from a life of consuming objects of industrial production. Seeking individual expression is also a quest for new forms and places of community. If the heated general stores and craftsmen’s workshops were the places where Germany’s social life unfolded in the postwar years, today’s urban community gardens and open workshops seem to be developing into hothouses of social solidarity for a post-fossil-fuel urban society.

In recent years, people of the most varied milieus have been joining forces and planting organic gardens in major European cities. They keep bees, reproduce seeds, make natural cosmetics, use plants to dye fabrics, organize open-air meals, and take over and manage public parks. With hands-on neighborhood support, urban gardening activists are planting flowers as they like at the bases of trees and transforming derelict land and garbage-strewn parking decks into places where people can meet and engage in common activities.

The new gardening movement is young, colorful and socially heterogeneous. In Berlin, “indigenous” city dwellers work side-by-side with long-time Turkish residents to grow vegetables in neighborhood gardens and community gardens; pick-your-own gardens and farmers’ gardens are forming networks with one another. The intercultural gardening movement is continuing to expand in striking ways, as seen on the online platform Mundraub.org, which uses Web 2.0 technology to tag the locations of fruit trees whose apples and other fruits can be picked for free (Müller 2011). Such novel blending of digital and analog worlds is creating new intermediate worlds that combine open source practices with subsistence-oriented practices of everyday life. (2)

Urban gardens as knowledge commons

Open source is the central guiding principle in all community gardens; the participation and involvement of the neighborhood are essential principles. The gardens are used and managed as commons even if the gardeners do not personally own the land. By encouraging people to participate, urban gardens gather and combine a large amount of knowledge in productive ways. Since there are usually no agricultural professionals among the gardeners, everyone depends on whatever knowledge is available – and everyone is open to learning. They follow the maxim that everybody benefits from sharing knowledge; after all, they can learn from each other, relearn skills they had lost and contribute to bringing about something new. Communal gardening confronts the limited means of urban farmers – whether in soil, materials, tools or access to knowledge – and transforms them into an economic system of plenty through collective ingenuity, giving and reciprocity. (3)

In urban gardens, both opportunities and the necessity for exchange arise time and again. A vibrant atmosphere emerges where the most varied talents meet. In workshops, for example, people can learn to build their own freight bicycles, window farming (4) or greening roofs; they can learn to grow plants on balconies and the walls of buildings, and use plastic water bottles for constant watering of topsoil. There is always a need for ingenuity and productivity, which often come about only when knowledge is passed along, which in turn releases additional knowledge.

Thus, the creative process in a garden never reaches an end. The garden itself is a workshop where things are reinterpreted creatively and placed in new relationships. One thing leads to another. It is not only the inspiring presence of the various plants that provides for a wealth of ideas, but also the ongoing opportunity to engage oneself and be motivated by the objects lying around (Müller 2011).

This is how a real community that uses a garden emerges over time. One of the most important ingredients for success is that the place is not predefined or overly restricted by rules. Instead, the atmosphere of untidiness and openness makes it apparent that cooperation and creative ideas are desired and necessary.

A new policy for (public) space

When the neighborhood people of Berlin-Neukölln tend their gardens on the site of the former Berlin-Tempelhof airport in plant containers they crafted themselves, bringing together people of many different backgrounds and generations and supported by the Allmende-Kontor, a common gardening organization, this is first of all an unusual use of public space. The garden consists of raised beds in the most varied styles on 5,000 square meters. Plants grow in discarded bed frames, baby buggies, old zinc tubs and wooden containers assembled by the gardeners themselves.

But more than an unusual public space, the Allmende-Kontor gardens underscore an important political dimension of urban gardening. The commons-oriented practices enable a different perspective on the city. They both require communities and at the same time create communities. People come together here, but not under the banner of major events, advertising or the obligation to consume. Instead, their self-organized, decentralized practices in the public realm implicitly express a shared aspiration of a green city for all. Yet no grand new societal utopia – “the society of the future” – is being promoted. Instead, simple social interactions slowly transform a concrete space in the here and now, building an alternative to the dominant order based on market fundamentalism (Werner 2011).

In other words, the policy preference for the small-scale as a rediscovery of one’s immediate environment is by no means based on a narrowed perspective. On the contrary: the focus is precisely on the overuse, colonization and destruction of the global commons, and for this reason, the local commons is managed as a place where one can raise awareness about a new concept of publicness (5) while simultaneously demonstrating that there are indeed alternatives – common usage in place of private property; local quality of life instead of remote-controlled consumption, as it were; and cooperation rather than individual isolation.

Managing the “internal commons”

The new focus on the commons in urban community gardens is not only a political defense of public space for its use toward the common good. At the same time, it is also a reclaiming of people’s internal consciousness and a rejection of the ascriptions of homo economicus, an image of humanity that reduces us to competition-oriented individuals whose attention is focused solely on their own advantage. (6) This overly simplistic model has been under constructive attack for some time, even in the field of economics. In particular, the social neurosciences have confirmed that people’s willingness to cooperate and need for connectedness are central elements of human nature. For scholars of the humanities, this is surely no new insight, yet it is still good to know that there is substantial scientific evidence showing that the existence of a boundary between mind and body, which is often used to justify hegemonic domination, is artificial, and that the interrelationships between body and mind are highly complex. For example, we know today that social or psychological experiences leave physical traces – even in our genes, as shown by epigenetics. Joachim Bauer considers this insight to be the decisive breakthrough regarding our concepts of humankind (Bauer 2008).

This has two consequences for the subject at hand: for one thing, a practice of the commons such as community gardening enables the gardeners to discover their bodies, the experience of having two hands and being able to create things with them. Such sensory experiences are directly connected to one’s grasp of the world. For another, the garden is the ideal place to learn how to cooperate. When designing a system to capture rainwater for the beds, for example, the experience reveals an aspect of being human – namely connectedness – that is just as important as the experience of autonomy (Hüther 2011).

In this sense, commons are a practice of life that enable even the highly individualized subjects of the 21st century to turn their attention to one another, and not least to slow down their lives. After all, time, too, is a resource to be conceptualized in the community. Experiencing time means being able to pursue an activity as one sees fit, enjoying a moment or spending it with others. By accelerating time to an extreme degree, digital capitalism has subjected virtually everyone to a regime of efficiency, with the result that people’s sense of time is determined by scarcity and by the stress people subjectively feel to “fill” time with as much utility as possible. Time is “saved,” leisure hours are regarded with suspicion, and the boundaries between work and free time are increasingly blurred.

The garden is an antidote that can be used as a refuge by the “exhausted self,” as described by French Sociologist Alain Ehrenberg. The garden slows things down and enables experiences with temporal cycles from a different epoch of human history, agrarian society. Small-scale agriculture, which is being rediscovered in many urban gardens, is cyclical in nature. Every year, the cycle begins anew with the preparation of the soil and with sowing. People who farm are exposed to nature, the climatic conditions, the seasons and the cycles of day and night. For city dwellers whose virtual lives have taught them that everything is always possible at the same time, and above all, that everything can be managed at any time, these dimensions of time are highly fascinating. Gardening enables the insight that we are integrated in life cycles ourselves and that it can have a calming effect to simply “give oneself up” to the situation at hand.

In other words, managing the commons creates not only valuable experiences, but also social relationships with far-reaching effects. And, one might add, they are valuable for achieving the transformation of an industrial society based on oil and resource exploitation into a society guided by premises of democratic participation that no longer “lives” on externalizing costs but, to the extent possible, avoids creating them in the first place. Processes of reciprocity and an “economy of symbolic goods,” as Bourdieu puts it, are just as important for highly differentiated modern societies as for premodern ones (Adloff and Mau 2005). Old and new practices of the commons offer inspiring options for action.

Urban agriculture: the new trends

Agropolis is the title of the planning concept of a group of Munich architects who won the Open Scale competition with a “metropolitan food strategy” in 2009. The concept for an “urban neighborhood of harvesting” places growing one’s own food, the valuation of regional resources and sustainable management of land at the center of urban planning. Harvests are to become a visible part of everyday urban life. If the city implements the model, fruit from the commons and community institutions that exchange, store and process the harvest could create the basis for a productive collaboration on the part of the 20,000 inhabitants of the new neighborhood.

The Citizens’ Garden Laskerwiese is a public park managed by the citizens themselves. A group of 35 local residents transformed the previously garbage-strewn, derelict land in Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg, in Berlin, into a park. They concluded a contract with the district authorities, agreeing that the citizens’ association is responsible for services such as tending the trees and the lawns on the site. In return, it can use parcels of land and beds for growing vegetables free of charge. Such new models that help cash-strapped municipalities shoulder their financial burden and expand the opportunities for people to shape public spaces require a lot of time and effort for communication on both sides.

The Allmende-Kontor (roughly: Commons Office) is an initiative of the Berlin urban gardening movement that has been tending community gardens on the site of the former airport Berlin-Tempelhof together with local residents since 2011. Raised beds of the most varied styles are being created on 5,000 square meters. The Allmende-Kontor considers itself as a garden for all – and at the same time as a place for storing knowledge, for learning and for consulting and networking Berlin community gardens. The establishment of a pool of gardening tools and a seed bank available for unrestricted use are being planned as well.

References

- Adloff, Frank and Steffen Mau, Eds. 2005. Vom Geben und Nehmen. Zur Soziologie der Reziprozität. Frankfurt/New York. Campus.

- Bauer, Joachim. 2008. Das Gedächtnis des Körpers. Wie Beziehungen und Lebensstile unsere Gene steuern. München. Piper.

- Hüther, Gerald. 2011. Was wir sind und was wir sein könnten. Ein neurobiologischer Mutmacher. Frankfurt. Fischer.

- Müller, Christa, editor. 2011. Urban Gardening. Über die Rückkehr der Gärten in die Stadt. München. oekom.

- Werner, Karin. 2011. “Eigensinnige Beheimatungen. Gemeinschaftsgärten als Orte des Widerstandes gegen die neoliberale Ordnung.” In: Müller, Christa, ed. a.a.O.: 54-75.

1. Berliner Zeitung, April 5, 2011.

2. Mundraub is described in Katharina Frosch’s essay in Part 3.

3. For more, read the conversation between Brian Davey, Wolfgang Hoeschele, Roberto Verzola and Silke Helfrich in Part 1.

4. Window farming is vertical gardening on a windowsill. Plants are grown in hanging plastic bottles, which also provide greenery for the windows.

5. See also Brigitte Kratzwald’s essay on social welfare in light of the commons in Part 1.

6. For more detail on this topic, see Friederike Habermann’s essay in Part 1

Christa Müller (Germany) is a sociologist and author. For many years she has been committed to research on rural and urban subsistence. She is executive partner of the joint foundation “anstiftung & ertomis” in Munich. Her most recent book (in German) is Urban Gardening: About the Return of Gardens into the City.

Next Event: the future of Urban Gardening

the future of Urban Gardening

Thursday, June 27, 2013

Location: Museum Geelvinck, Keizersgracht 633, 1017 DS Amsterdam

The conference language is English.

This event is in collaboration with the Museum Geelvinck

The speakers and topics are

Wouter Schik, Landscape architect, Arcadis

Creating tomorrows green livable cities

Rachelle Eerhart, Project leader, IVN – Institute for Nature education & sustainability

Urban farming: getting back in touch with our food

Vincent Kuypers, director of theSolidGROUNDS, knowledge brokers for green economy

Parksupermarket

Tom Bosschaert, Founder & Director, Except Integrated Sustainability

Urban farming as green engine for urban redevelopment

Our moderator is Tarik Yousif, Presenter at the Dutch public broadcaster NTR

Insight on Conflict

Insight on Conflict provides information on local peacebuilding organisations in areas of conflict. Local peacebuilders already make a real impact in conflict areas. They work to prevent violent conflicts before they start, to reduce the impact of violence, and to bring divided communities together in the aftermath of violence. However, their work is often ignored – either because people aren’t aware of the existence and importance of local peacebuilders in general, or because they simply haven’t had access to information and contacts for local peacebuilders. We hope that Insight on Conflict can help redress the balance by drawing attention to the important work of local peacebuilders. On this site, you’ll be able to find out who the local peacebuilders are, what they do, and how you might get in touch with them. Over half the organisations featured on Insight on Conflict do not have their own website.

“Donors are struggling for information such as this. The security situations in these countries mean that international staff postings are one to two years at the most. In the case of Pakistan, we go from crisis to crisis (floods, assassinations, large scale terrorist attacks) and staff are usually caught up in the reactive work that these situations generate. As a result, we struggle with transfer of institutional memory regarding credible local organisations and everyday conflict events (which when analysed make sense of our bigger issues). In donor and civil society circles we also talk increasingly about bringing our efforts together to have a greater impact on the issues we work on. People still struggle though, with making the connections and placing their initiative within the larger context of social sector work taking place. Lastly, although we admit the issues associated, due to lack of information we struggle with the ‘entrenched partners’ phenomenon i.e. we continue to work with local organisations on our radar, rather than branching out and taking calculated risks.”

Conflict areas – some examples:

Victim of landmines in Colombia. Photo credit: Sgiraldoa

Colombia

Colombia has experienced an intense intrastate conflict for over half a century. Whilst guerrilla groups have suffered several high-profile setbacks, they are still a powerful force and hostilities are not expected to cease in the near future.

Paramilitary demobilisation has been successful in many but not all areas. The armed conflict is fuelled by drug-related violence, organised crime and tensions with neighbouring Ecuador and Venezuela, which have been accused of supporting rebel groups. Relations with Venezuela, in particular, have worsened over recent months.

Former President Álvaro Uribe Vélez, who served since 2002 and operated a hard-line stance against the guerrilla forces and consistently maintained one of the highest approval ratings of any Latin American presidency, despite criticisms from human rights groups; has been replaced with Juan Manuel Santos, a former Defence Minister. Given his key role in the Uribe administration, security policy continuity is anticipated.

Peacebuilding organisations

Conflict Profile

Colombia is in the midst of an almost 50-year conflict between the government and several guerrilla groups. The human impact of the conflict has been enormous, with at least 50,000 lives lost to date, and one of the world’s largest populations of internally displaced people – many of whom have disappeared.

Photo credit: United Nations

Sudan and South Sudan

The conflict in Sudan has many faces, the best known are a ‘North-South’ conflict, ‘that problem in Darfur’ or an ‘Arab-African’ conflict. The reality is that Sudan is deeply complex with many isolated but often overlapping conflicts that blur common perceptions.

Local realities

The fragile Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) which was reached in 2005, in one way or another, affects almost every state in the North and South of Sudan. Beneath that numerous tribal differences that continue to be politicised, and bitter oil related conflicts, exacerbate problems further. Such complexities make it almost impossible for outsiders to fully understand, once again highlighting just how indispensable local peacebuilders are. There are fears that the conflicts in Sudan have the potential to trigger a regional war, drawing in neighbouring countries.

Since the referendum

As the question of South Sudan’s (in)dependence is one of the major disputes dividing North and South, a Referendum, conducted in response to the 2005 Naivasha Agreement (Comprehensive Peace Agreement) between the NCP and SPLM, was held on the 9th January 2011 to decide whether South Sudan should remain part of Sudan or become autonomous. A similar referendum was to be held in Abyei to decide whether it joined the North or South, but was postponed due to complications.

Significant problems predicted before the Referendum have since surfaced. Darfur has reemerged as conflict region, with a sharp rise in violent clashes being reported. New splinter rebel groups have taken shape and are contesting fresh demands in the South and East. The fate of the oil rich border states are still undecided, with the possibility of renewed violence. Thousands of refugees have fled conflict areas. And logistics over citizenship and the splitting of the national debt have yet to be worked out. These problems threaten to derail the entire process.

Yet steps are being taken towards resolving these issues facing the creation of the world’s newest nation. Peace talks over a planned referendum in Darfur are under way, ex-combatant reintegration is taking a foothold and South Sudan’s draft constitution has successfully been completed. It has yet to be seen in how long and with how much difficulty the secession is to be instated.

Peacebuilding organisations

Conflict Profile

On 9 July 2011 Sudan split in two creating the world’s newest nation – the Republic of South Sudan. South Sudan’s independence was the final stage of a 6 year peace agreement ending decades of civil war. However, peace is not yet guaranteed. As the South gains statehood, crucial issues such as border demarcation, sharing of debt, and oil revenues and the use of the North’s pipeline remain unresolved. Fighting in South Kordofan, Blue Nile, and Abyei threatens the stability of the peace, and there is ongoing tensions and violence on both sides of the border.

Problems are not confined to tensions only along the border. Less dramatic, but arguably more damaging is the serious rise in food and water prices, the lack of medical care and infrastructure, significant IDP flows, and poorly functioning economy of the South. These developments daily endangering lives simply through lack, and encourages reckless and desperate behaviour that can lead to violence. Both countries have significant internal conflicts to deal with. Decades of violence during the North-South civil war followed by a fragile peace agreement mean that legacies of violence remain and numerous localised conflicts continue. Darfur has caught the world’s attention. While the South is facing multiple rebel groups in the border states of Unity, Jonglei, and Upper Nile.

Club of Amsterdam blog

Club of Amsterdam blog

http://clubofamsterdam.blogspot.com

Oh, The Humanities! Why STEM Shouldn’t Take Precedence Over the Arts

The Egg

Joy Rides and Robots are the Future of Space Travel

The Transposon

10-step program for a sick planet

Public Brainstorm: Economic-Demographic Crisis

Public Brainstorm: Energy

Public Brainstorm: EnvironmentPublic Brainstorm:Food and WaterPublic Brainstorm: Overpopulation

News about the Future

Africa Competitiveness Report 2013

The Africa Competitiveness Report 2013 comes at a time of growing international attention on Africa as an investment destination and increasing talk of an African economic renaissance. It is the fourth report in this series to leverage the knowledge and expertise of the three partnering organizations – the African Development Bank, the World Bank Group and the World Economic Forum – to present a joint policy vision for Africa. Under the theme Connecting Africa’s Markets in a Sustainable Way, this year’s report explores how Africa can connect its markets and communities through increased regional integration as a key to raising competitiveness, diversifying its economic base and creating jobs for its young, fast-urbanizing population.

Through a comprehensive analysis of Africa’s most pressing competitiveness challenges, the report discusses the barriers to increased trade, including the state of Africa’s infrastructure and its legal and regulatory environment. It similarly considers how innovative public-private partnerships, often anchored to potential growth poles, can serve as incubators for self-sustaining industrialization, more jobs, greater opportunities and more dynamic regional integration. The report includes detailed competitiveness profiles for 38 African countries, providing a comprehensive summary of the drivers of productivity and competitiveness in countries across the continent.

STRAWSCRAPER – an urban power plant

STRAWSCRAPER is an extension of Söder Torn on Södermalm in Stockholm with a new energy producing shell covered in straws that can recover wind energy.

The straws of the facade consist of a composite material with piezoelectric properties that can turn motion into electrical energy. Piezoelectricity is created when certain crystals’ deformation is transformed into electricity. The technique has advantages when compared to traditional wind turbines since it is quite and does not disturb wildlife. It functions at low wind velocity since only a light breeze is sufficient for the straws to start swaying and generate energy. The existing premise on top of the building is replaced with a public floor with room for a restaurant. The new extension creates, a part from the energy producing shell, room for the citizens with the possibility to reach a lookout platform at the very top of the tower with an unmatched view of Stockholm.

The EU: the third great European cultural contribution to the world

By Huib Wursten and Fernando Lanzer, itim International

You can download the full report: click here

The future of the EU and of the Euro are dominating the headlines in all media. The cover of the Economist read: “Staring into the Abyss: a special report on the future of Europe” some time ago. The situation since then has changed very little.

The influence of culture has not been part of the analyses one sees in the media. Yet there can be no truly intelligent analysis of the situation unless one takes into account that there are huge differences in terms of the underlying assumptions, expectations and values of the stakeholders involved, in Europe and abroad.

The main focus of this paper will be to demonstrate that:

- Europe is the most diverse cultural continent in the world.

- The diversity in value dimensions found by empirical research has profound influence on the way people organize themselves in the EU nation states. These values lead to sometimes opposing views on centralization/decentralization, the rule of law, human rights, the separation of powers in a democracy and as a consequence the position of the Central Bank, the definition and role of leadership, the degree of sympathy for social cohesion, the answer to economic crisis: investing or austerity programs, etc.

- Five of the 6 possible models of organizing a nation state are to be found in the EU. Bridging these differences is a political and intellectual challenge of unique proportions.

- The way Europe is trying to bridge the value differences between nation states without imposing one model is a laboratory for solving similar challenges for a globalizing world.

- If the Europeans will be successful this will be a cultural change comparable with two previous European revolutions: the renaissance (the discovery of the individual) and the Enlightment, the period where individuals were empowered to think for themselves and not to accept blindly (religious ) authorities

I. Introduction

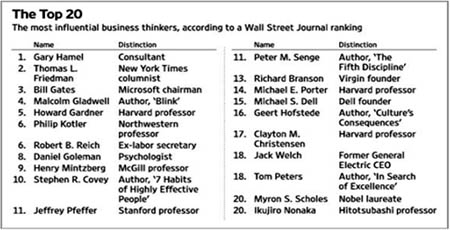

Professor Geert Hofstede is nowadays widely recognized as the one who did the most fundamental research on cultural differences. He carried out fundamental research into the dominant values of countries and the way in which they influence behavior in organizations. Original data were based on an extensive IBM database for which between 1967 and 1973, 116,000 questionnaires were used in 72 countries and in 20 languages.

The results were validated against about 40 cross-cultural studies from a variety of disciplines. Analyzing his data, Hofstede found five value clusters (or “dimensions”) being the most fundamental in understanding and explaining the differences in answers to the single questions. He measured the differences and calculated scores for 56 countries on these 5 dimensions. Later research partly done by others have extended this to 85 countries. The combined scores for each country explain variations in behavior of people and organizations. The scores indicate the relative differences between cultures.

The five dimensions of national culture identified by Hofstede were: power distance (PDI), individualism/collectivism (IDV), masculinity/femininity (MAS), uncertainty avoidance (UAI) and Long Term Orientation (LTO)

See below for a definition and short description of the five dimensions.

[…]

III. The Situation in Europe

Is one cluster more effective than others?

Because of “culture bias”, every member of a culture tends to think that their culture is better than all others, it’s a natural phenomenon. All international studies suffer from the same malady: they start by defining comparison criteria and fail to realize that their choice of criteria is influenced by the cultural values of the research team.

Outside looking in

Whenever any analysis of the European situation is made, we need to take into account the cultural background of whoever is making that analysis. We all have our own cultural bias, based on our own background.

Whenever Europe is observed by analysts coming from a Contest culture, such as the US and the UK, it is very likely that they will consider the European Union to be hopelessly mired in never-ending, inconclusive discussions. To the Americans and British observers, the European decision-making process will always be perceived as being too slow and not action orientated enough. These observers would like to see European leaders behaving in a more decisive way. Subconsciously, they hope to see a “heroic” type of leader who would cut through the complex discussions and would quickly reach a tangible result. They tend to underestimate the complexity of dealing with five different culture clusters, since they, themselves, deal with a much more homogeneous cultural reality, by comparison.

But is the UK looking at Europe from the outside or from the inside? Is the UK not part of Europe? Actually, it depends on who you ask: people everywhere perceive the UK as being part of Europe, except that the people in the UK themselves have a different opinion…

One could argue that every country in the EU faces the same dilemma: national independence and autonomy versus European integration and belonging. The dilemma is felt more strongly in the UK than anywhere else, due to the Contest nature of the UK culture. And the UK has the only Contest culture in the EU.

The eye of the beholder will always influence the analysis and its conclusions. When Europe matters are observed by Latin Americans and Africans (Pyramid cultures) it is very likely that the analysts will remark that the European Union lacks a strong, charismatic leader wielding enough authority to decide what is better for the greater good of the region. The only way to solve the EU’s problems, according to this perspective, is to give more authority to the European bureaucracy in Brussels and to appoint a European President/Prime Minister/King to run the Community. The title is not important, but having true authority which is respected by all, is essential.

From yet another perspective, the Germans see the EU as lacking in order and structure. They criticize the lack of legislation and the discipline to follow established rules. Whenever there are conflicts among European member-states, the Germanic cultures will recommend more structure and more discipline.

The Dutch and Scandinavians see the EU as a complex network of relationships among different member-states, who must all be heard and regarded as having equal rights, regardless of the differences in the size of their economies. They will often criticize the lack of conclusion to discussions, but will rebel against any attempt to impose authority from the centre or to disregard the less powerful member-states.

The French, Belgians, Italians and Spanish (Solar-System cultures) will be split internally. In theory, they tend to advocate greater authority from the centre; at the same time, that goes against their own interests to maintain autonomy. They will recommend greater central authority as the only way to resolve issues and will engage in fierce lobbying to defend national interests, often appearing to contradict themselves.

Finally, the perspective of the only cluster that is not found in Europe, the “Family” cultures. They will look puzzled at Europe. The Chinese for instance will criticize Europeans for lacking respect for authority and for being selfish individuals, rather than sacrificing personal interests for the greater good. Yet, the Chinese are patient, their culture values looking at things from a long-term perspective. To them, what is happening in Europe is just “a hiccup” in a long process of development, which will require another century or so to play itself out. What is most amusing to the Chinese is how people can expect European integration to happen so “quickly”… They would expect it to take at least a century.

IV. Europe In 2022

Looking at the future and making forecasts is always a daring endeavour… Most predictions made by economic analysts turn out to be mistaken after just a couple of years. This may very well be because most economists (if not all) fail to incorporate culture factors into their analyses. They usually fail to recognize their own culture bias, and they proceed to analyse and predict economic behaviours in other cultures without taking culture into account. Small wonder that people fail to behave according to such forecasts.

If we take in consideration the culture perspective and its influence on political, sociological and economic aspects of our analysis, and then look at what is likely to happen in Europe during the next decade, perhaps our forecasts can be “less inaccurate”.

The main challenge for Europe in the next ten years will be to make further progress towards economic and political integration, while simultaneously recognizing different culture identities and managing them. Not a small thing…

We are talking about a completely new paradigm. A system that can transcend nation states with different value preferences.

Nation: people sharing a certain territory and having a shared national consciousness who in principle accept the authority, legitimacy and power of their political administration (= state)

The inherent contradiction about the European Union is that further integration requires relinquishing some forms of local authority, legitimacy and power at the national level to empower a central government of the whole region. This runs contrary to the values of the UK, the “Machine” cultures and by the Dutch and Scandinavians, although these latter, as “Network” cultures, are more willing to accommodate things as long as there remains a sense of equality among all member states and dissenting opinions are heard (but not necessarily acted upon…).

The French, Belgians, Italians, Spanish and Polish (“Solar System” cultures) will go along with the idea, but they know very well that discipline requires authority and frequent inspections to be enforced. The aspects of contention will be that they will favour more power to the central government, but will fight to exert each their own influence in it, while avoiding that such a government would, in practice, have authority over their own national government. They will try to include “exemption” and “exception” provisions (supported by the British), but these will face resistance from the Germanic cultures.

We can expect that Germany will continue to push for establishing a structure, a set of processes and procedures to which all member-states will abide. Austria and Hungary are both extremely likely to support most German endeavours. However, the Germans will tend to emphasize that it is up to each member-state to enforce the rules, or to have an “automatic mechanism” which kicks in to ensure fiscal discipline is observed. They do not like a process which requires frequent inspections, as this goes against the values of low Power Distance. The Germans (and the other “Machine” cultures) take for granted that people will focus on performance, naturally, and that everyone will do their best to avoid deviations from established plans. They are very likely to be disappointed in relation to these aspects.

The Portuguese and Greek (“Pyramid” cultures) will support a strong central government as long as they perceive it to really have authority. Half-baked measures and “compromise” solutions will not gain their respect, so in those cases they will pay lip service to integration but will pursue different agendas at the local level whenever they can get away with it. Long discussions and compromises in Brussels will be perceived as signs of weakness at the centre, giving them implicit endorsement to find their own ways. This will be enhanced in the absence of frequent inspections.

The UK, of course, will remain the last bastion of euro-scepticism. They tend to feel comfortable with American ideas. They are comfortable operating under a less regulated environment and maintaining “local” autonomy. The only way Britain might agree to more integration and a stronger European Union government is if they perceive it as leading to better performance and higher yields for Britain. As it stands, there is very little motivation in the UK population to support the EU: the situation in Britain would have to get much worse, so bad that relinquishing authority to Europe would seem like the “lesser evil”. Perhaps, if the first “European Prime Minister” would be a British national with a ten-year mandate, that might make a difference.

Overall, the key issue of the political union and the monetary union is subsidiarity. This defining principle in the Maastricht treaty needs rethinking. Only these things should be decided on the higher that cannot be decided on the lower level was and is a sound principle. However, too much pressure has been on giving up autonomy and top down regulating. In the process, the reality of value diversity has been neglected. As a consequence the needed legitimacy of the democratic political system is under pressure. This is dangerous because a lot of people in the EU nation states don’t recognize their reality any more in the decisions taken by the “centre”.

To be successful and to maintain the trust of the voters of the nation states, the need to centralize further because of the pressure of the “market” should be weighed carefully. Further steps might be necessary in the technical/ rational reasoning. But this is not purely technical/ rational. This is about bridging fundamentally different values preferences. This never has been done in the world. This is an exciting, giant new step. It is only to be compared with the cultural impact of Renaissance and the Enlightment

V. Conclusions

Culture is having a defining role in the choices people make also in the political environment. Culture is closely linked to national identity and individual identity. One cannot discuss political and economic systems without considering the impact that culture has on both of those.

This is not a matter of development. Also in highly developed, democratic countries one can see these differences.

In no way one can say that one economic or political or legislative model is per definition better than others.

It is dangerous to import systems fitting one type of culture into other value systems without taking this into account.

For European integration to continue making progress, a number of concessions will need to be made, by all parties involved ,to the five different set of expectations and values (culture clusters) existing among the member-states. Trying to impose one set over the other four is likely to result in a stalemate.

And yet the EU is a fascinating experience in the social organization of mankind, with far-reaching consequences for the whole world watching on the sidelines.

Is it possible to transcend the concept of nationalism? Are we witnessing, in the EU, the birth of a new concept, which will succeed nationalism and predominate over the next 200 years?

If we are experiencing a major transition in Europe towards a different form of social organization, we must realize two things, above all else:

a) it will be traumatic;

b) it will take time

Such a transition will not be smooth; conflicts are to be expected. Movements forward will be followed by a couple of backward steps. Yearning for the future will be accompanied by yearning for the past. Millions of people will be involved in discussing the inherent dilemmas of the situation.

Such a transition will take decades to develop, whatever the outcomes. Perhaps historians in 2100 will look back at this period as “The European Transition”, from 1990 to 2030…

What could we do, as leaders in Europe, to mitigate the risks and minimize the disruption which affects millions?

A set of recommendations

1. Angela Merkel once summarized the dilemma by asking “Do we want more Europe or less Europe?”. In considering the response to that question, we need to go beyond the usual use of Rationality which is typically employed by economists and most pundits. We need to look at Emotions and Values, beyond Rationality. This is the first recommendation: look at Values (that is where the essence of Culture resides) and the Emotions involved, in addition to Rational arguments. The people of Europe will not reconcile the basic dilemma based on Rationality alone. The other two aspects (Values and Emotions) are equally important in considering the available options to reconcile the dilemma.

2. Think “outside the box”. If we are creating a new form of social organization, we need to develop new mechanisms and policies touching every aspect of social life. We will not solve 2020 problems using 1930’s politics and economics. New forms of democratic representation may be needed, not just the European Parliament, which is nothing more than an international version of the national parliaments, in themselves out-dated institutions desperately needing replacement. New concepts in economics need to govern economic discussions, such as Behavioral Economics, Sustainable Economics and other emerging schools of economic thinking. New regulations need to be developed to replace the old ones which date from several decades ago.

3. People need to feel that they belong to a community sharing similar values (similar culture, notions of what is “right” and “wrong”). Surely it must be possible to provide that sense of identity and belonging to the next generations without necessarily having to say “you are German, but I am English”. Actually, this feeling of belonging and identity is often provided more strongly by a community much smaller than a nation. People feel “Bavarian” rather than “German” or they feel “Scottish” rather than “British”. The point here is that it should be possible to share the same currency, fiscal policies and broad social policies, as in a true federation, while maintaining relative autonomy and cultural differentiation, probably in a more fractioned sense than in the current 27 nation-states. Perhaps cultural identity must be preserved in 54 sub-national regions, or even more. This needs to be explored with an open mind. The core issue is that culture needs more differentiation while economics and politics need more integration. These things are not mutually exclusive, but they require some creative thinking to co-exist.

4. Transnational and supranational discussions need to be fostered. If we have the Germans discussing amongst themselves whether they want “more Europe or less Europe”, while the Greeks hold the same discussion in parallel only amongst themselves, the whole process tends to foster disintegration. Issues need to be increasingly discussed across national borders and not restricted by them. The EU leaders need to think like EU leaders and not like national leaders, and they need to facilitate European discussions rather than national discussions.

5. Huge transnational education programmes need to be put in place to foster integration in a truly democratic and open way. This should not be propaganda or brain-washing, but rather genuine open discussions and sharing of information, values and emotions. Currently, this open exchange of Rational, Emotional an Ethical aspects is happening informally, with no planning or coordination, through tourism, business interaction and social networks. It should be accompanied by intelligent programmes in mass education using a 21st Century approach.

6. Subsidiarity needs to be on the agenda again. The principle is right: as much as possible should be decided on the lower levels. This needs strong restraint from the bureaucrats in the centre. This needs to be reflected in the choice of “leaders”. Individuals are not always reflecting the values of the culture they are coming from. Still it is strange and bad for the perception of citizens to see that so many visible leaders in the EU and in the Monetary Union are from the high PDI, high UAI countries (see below). Meaning from cultures like Italy, France, Spain, Portugal and Belgium favouring centralization.

7. Next to Federal institutions like the ECB it is necessary to develop more consistent inter-governmental forms of administration. We believe that the culture clusters are defining the countries that are like minded. That would create a system allowing for the necessary social diversity in a unified Europe.

Other recommendations need to be developed, discussed and implemented. The huge social transformation in Europe is more than an experiment in a certain continent: it is a major stage in the social development of mankind.

Dismantling the European Union will not stop the integration process of our societies all over the world: it will merely delay it for a couple of decades. We should be able to manage the integration process better, beginning in Europe, which is most advanced in these matters, learning from that process and applying the learning in other parts of the world.

The only way to do that will be to go beyond the Rational and to look at Culture and its emotional consequences in order to reconcile the dilemmas involved.

Short description of the five “Hofstede” dimensions.

- Power distance is the extent to which less powerful members of a society accept that power is distributed unequally. In large power-distance cultures everybody has his/her rightful place in society, there is respect for old age, and status is important to show power. In small power-distance cultures people try to look younger and powerful people try to look less powerful.

It’s the opinion of the author of this article that this dimension creates about 80 percent of the problems in international organizations that are trying to operate with multicultural teams.”People in countries like the US, Canada and the UK score low on the power-distance index and are more likely to accept ideas like empowerment, matrix management and flat organizations. Business schools around the world tend to base their teachings on low power-distance values. Yet, most countries in the world have a high power-distance index. - In individualistic cultures people look after themselves and their immediate family only; in collectivist cultures people belong to in-groups who look after them in exchange for loyalty. In individualist cultures, values are in the person, in collectivist cultures, identity is based on the social network to which one belongs. In individualist cultures there is more explicit, verbal communication; in collectivist cultures communication is more implicit.

- In masculine cultures the dominant values are achievement and success. The dominant values in feminine cultures are caring for others and quality of life. In masculine cultures performance and achievement are important. Status is important to show success. Feminine cultures have a people orientation, small is beautiful and status is not so important.

- Uncertainty avoidance is the extent to which people feel threatened by uncertainty and ambiguity and try to avoid these situations. In cultures of strong uncertainty avoidance, there is a need for rules and formality to structure life. Competence is a strong value resulting in belief in experts, as opposed to weak uncertainty-avoidance cultures with belief in practitioners. In weak uncertainty-avoidance cultures people tend to be more innovative and entrepreneurial.

- The last element of culture is the Long Term Orientation which is the extent to which a society exhibits a pragmatic future-orientated perspective rather than a near term point of view. Low scoring countries are usually those under the influence of monotheistic religious systems, such as the Christian, Islamic or Jewish systems. People in these countries believe there is an absolute truth. In high scoring countries, for example those practicing Buddhism, Shintoism or Hinduism, people believe truth depends on time and context.

Repeated research is showing that these values and the scores of countries are not, or very slowly, changing over time.

– A Danish scholar, M. Søndergaard, found 60 (sometimes small scale) replications of Hofstede’s research. A Meta analyses confirmed the five dimensions and the scores of countries.

– A recent replication, showing the same result was carried out by including Hofstede’s questions in the EMS, the European Media & Marketing Survey.

Books

Culture’s Consequences, International Differences in Work-Related Values (Cross Cultural Research and Methodology) by Geert Hofstede

Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions and Organizations Across Nations by Geert Hofstede

Masculinity and Femininity: The Taboo Dimension of National Cultures (Cross Cultural Psychology) by Geert Hofstede

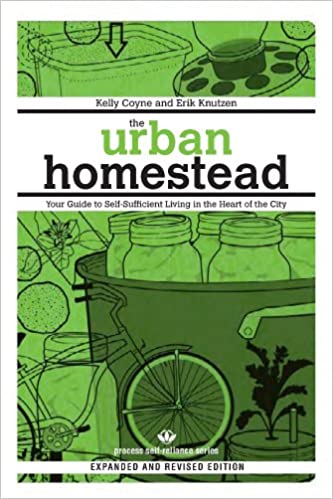

Recommended Book

The Urban Homestead: Your Guide to Self-Sufficient Living in the Heart of the City

By Kelly Coyne (Author), Erik Knutzen (Author)

This celebrated, essential handbook for the urban homesteading movement shows how to grow and preserve your own food, clean your house without toxins, raise chickens, gain energy independence, and more. Step-by-step projects, tips, and anecdotes will help get you started homesteading immediately. The Urban Homestead is also a guidebook to the larger movement and will point you to the best books and internet resources on self-sufficiency topics.

Written by city dwellers for city dwellers, this copiously illustrated, two-color instruction book proposes a paradigm shift that will improve our lives, our community, and our planet. By growing our own food and harnessing natural energy, we are planting seeds for the future of our cities.

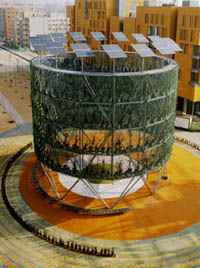

Agricultural Urbanism Lab

The Agricultural Urbanism Lab (LUA) was created in 2012 by SOA, an architectural practice, Le Sommer Environnement, a consultancy specialised in environmental engineering in architecture and Le Bureau d’Etudes de Gally, specialised in landscape and plant and agricultural innovation. LUA is a platform for reflection and exchanges aimed at promoting and developing agricultural urbanism, and defines itself as a collaborative structure bringing together its members’ competences and efforts for innovative projects. Regarding the city as a sustainable environment in the fullest sense, the Agricultural Urbanism Laboratory places man at the heart of its reflection.

The Agricultural Urbanism Lab is a collective, multi-disciplinary project drawing on comprehensive, wide-ranging analyses. Estimating the limits of compatibility between intensive farming and the urban environment involves a variety of different disciplines:

- the choice of plant species, growing methods, productivity and quality: agriculture and agronomy

- health and energy exchanges with the city: environmental engineering

- the future of an endangered profession and the prospects of dynamizing it in an urban context: sociology and economics and the rural world.

- the reduction of transport, distribution methods: economics and regional development strategy.

- the long-term evolution of the concepts of verticality and locality, the aesthetics of the urban environment, traceability in the food industry and taste: philosophy

- the questions of real estate, the creation of urban and peri-urban areas, the advantages of a mixed urban environment and the image of industry within it: urbanism and demography.

The implantation of farms in urban areas on very different scales will introduce de facto a diversity hitherto almost inexistent in peri-urban zones and in the country.

Our studies show in what proportions this form of agriculture can complement rural production and perhaps contribute to improving the quality of production en general.

The HEQ (High Environmental Quality) label sets fourteen environmental optimisation targets, but there should also be a “HHQ” (High Human Quality) label. Because the city is first and foremost a human environment, whose functioning and richness depends on the cohesion of its multiple social groups.

The urban farm can only have real legitimacy if it represents a social entity, on the scale of an individual producer, cooperative or company, and engages in a direct, local exchange with the population. One could thus envisage a dynamic comparable to the organisation of the “green belts,” surpassing merely mercantile concerns and redefining the role of the farmer.

Agricultural progress once consisted in freeing a proportion of the population from agricultural tasks for employment in industries and services, and reducing physical effort by mechanisation and the use of chemicals. The urban farm will in turn promote the farmer’s profession and restore its responsibilities, both in its production choices and in its role in passing on knowledge and skills. The aim of our studies is to prioritise movement of people rather than the transport of merchandise.

Finally, the prospect of agriculture in the city enables one to imagine a new urban landscape capable of satisfying our social need for nature.

Projects by members:

Centre commercial Atlantis à Nantes. Le Bureau d’Etudes de Gally

La Galerie. Le Sommer Environnement

La Tour Vivante. SOA

The Living Tower is a high-rise office and apartment building with its own market gardening units. It therefore combines food production and consumption and living spaces. The interweaving of these programmes entails their respective adaptation and creates various types of exchanges. Their interlacing rather than mere superimposition expresses the fusion of the tower’s programmes (housing units/offices and crops) but the arrangement of the housing units is complexified and the light exposure of the agricultural units isn’t optimised. Each programme adapts to the other: the housing units enable the integration of the growing areas, and the farm recycles the building’s waste and feeds its inhabitants. The Living Tower has a 900 m2 footprint, thirty storeys and an agricultural surface of 7,000 m2 deployed along a continuous 875-metre band.

Urbanana. SOA

Urbanana is a farm producing a wide variety of bananas currently unavailable on the European market due to ripening and transport constraints. It has its own research laboratory and exhibition space promoting awareness of the banana industry. Using grow lights rather than natural lighting, its implantation in the city has few constraints and it can discreetly adopt the scale and format of the surrounding urban fabric. When housed between residential buildings, it is primarily a façade project.

Futurist Portrait: Stuart Candy

Stuart Candy – Foresight and Innovation Leader at Arup Australasia, Adjunct Professor at California College of the Arts, and Research Fellow of The Long Now Foundation.

Dr Stuart Candy is Foresight + Innovation Leader for Arup Australasia. Currently based in Melbourne, he has brought his unique take on futures to diverse subjects and settings. Internally these have included a collaborative research project on the Food-Energy-Water resource nexus; a briefing to the UKMEA Board on Britain’s economic outlook; advice on process design for the biennial Australasia Regional Forum; and strategic conversation around the organisation’s “Ecological Age” vision.

His experience also includes client-facing engagements with national, state and municipal governments; the Sydney Opera House, General Electric, and IDEO; lectures at UC Berkeley, New York University, and the Royal College of Art; workshops at Yale, Singularity University, and the TED Conference; and an installation at the California Academy of Sciences for Jacques Cousteau’s 100th birthday.

Stuart works at the intersection of design and foresight, and has an international reputation in the collaborative design of experiential futures – translating scenarios into immersive situations and tangible artifacts. He was an advisor to the Future We Want project for the United Nations Rio+20 summit, held in June 2012, and to the inaugural Festival of Transitional Architecture (FESTA), staged in Christchurch in October 2012.

He holds degrees in Arts and Law from the University of Melbourne, and a PhD from the Alternative Futures program of the University of Hawaii at Manoa, where he was twice awarded the East-West Center’s Graduate Degree Fellowship. As Adjunct Professor at California College of the Arts, Stuart created the Strategic Foresight course for CCA’s groundbreaking MBA in Design Strategy. He blogs at the sceptical futuryst and is @futuryst on twitter.

Stuart Candy: “In my view the ‘product’ of foresight done properly is what could be called (echoing Antonio Gramsci), optimism of the will. This can be contrasted with optimism of expectation. Doing futures work cultivates in oneself, and ideally in one’s companions, an awareness of how things could be different, and with that, a sense of one’s increment of responsibility.” – from an interview by Heath Killen, Desktop

Agenda

| Season Events 2012/2013 June 27, 2013 the future of Urban Gardening Location: Geelvinck Museum, Keizersgracht 633, 1017 DS Amsterdam Supported by Geelvinck Museum  |

Customer Reviews

Thanks for submitting your comment!